From the top floor of The Venetian, the biggest casino in the former Portuguese colony of Macau, behind the big crystal windows that grace the golden facade of the skyscraper, the view of the Pearl River Delta is breath-taking.

Behind the morning mist on the horizon hides, the global financial centre of Hong Kong, one of the most densely populated cities in the world and a fulcrum of exchange between goods and people from every corner of the world.

In 2016, the two sides of one of the wealthiest regions in China will be linked by the longest bridge in the world: 50 kilometres of viaduct, artificial islands and underwater tunnels at an estimated cost of $10.6 billion.

The National Development and Reform Commission of Hong Kong deems it a necessary project: it foresees from 180 million to 240 million vehicles crossing it from the day it opens to 2020.

The bridge will open a second link between Hong Kong and mainland China after the highway to Shenzhen, which has become the most trafficked artery in the world. The bridge will reduce the distance that drivers must endure between Hong Kong and Macau from 160 kilometres to 30 kilometres.

Evolution of the Bridge

Since the second half of the 1700s with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, bridges have undergone a profound transformation thanks to the evolving methods of construction led by great engineers and architects such as Navier, Cauchy and Poisson.

In England alone, the number of bridges increased from 30,000 to 60,000 during the first half of the 1800s. In addition to technical changes, the new ways of building bridges adopted new materials, the most common of which was iron. It remained the preferred material up until the end of the 1800s when steel was introduced with the first suspension bridge in Brooklyn.

Today, the characteristics of a bridge that have come to dominate are its length and its sense of grandeur. The latest engineering techniques and the further evolution of materials allow for the realisation of dreams to connect distant lands.

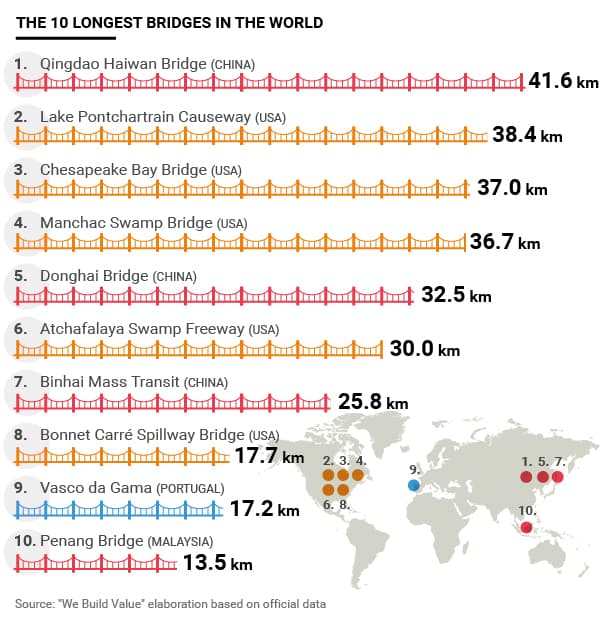

Looking at the world’s three longest bridges, their statistics are impressive. The third longest, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, in Maryland, measures 37 kilometres.

The second is in Louisiana: the Causeway Bridge over Lake Pontchartrain that runs for 38.40 kilometres between the cities of Mandeville and Metairie near New Orleans.

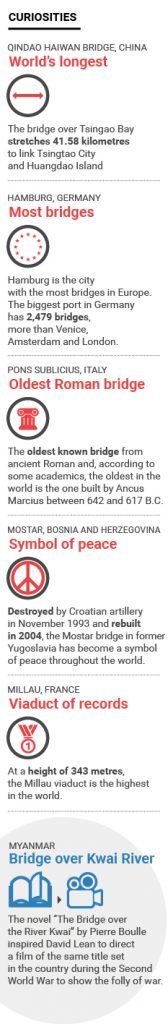

But the record for the longest bridge in the world - before the title is taken by the one between Hong Kong and Macau - is held by the Qingdao Haiwan Bridge in China. It is 41.58 kilometres long and links Qingdao with the island of Huangdao. Not only is it a big, important structure for commerce in the entire region but also a symbol of the construction prowess of a country that managed to complete it in only four years, from 2007 to 2011.

Motors of the economy

Men and vehicles are not the only things that cross bridges. Economies do as well, given the impact that this type of infrastructure has on local communities. On this point, the United States has historically been at the forefront, incorporating infrastructure into its vision of transforming the country into an engine of growth.

This is the sense that comes from the latest bridge that will connect the country with Canada. The U.S. administration says it will have the greatest impact on international trade in the world.

The Gordie Howe International Bridge will connect Windsor, Ont. with Detroit, Mich., after a $950 million investment. It is the latest example of the use of resources for a specific purpose: increasing trade between two regions and creating business opportunities. Such is the importance of the project that President Barack Obama signed a presidential decree last March to begin work on the new bridge.

The United States knows full well the impact that bridges have on the economy. Its bridges facilitate the crossing of tens of millions of vehicles every day, representing an exceptional instrument for the flow of goods and people. This enormous movement of traffic – as explained in a report by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (for further details, read the article on the bridges of New York City) – guarantees an immediate economic return. Every dollar spent on infrastructure like bridges and roads, it says, results in $2 of growth in the gross domestic product of the region served by that infrastructure.

Mostar: Bridge as symbol

The strength of a bridge does not only reside in its ability to enable the flow of traffic and commerce but also in the way it lends itself to being a symbol of encounter and integration of two peoples and cultures. The Mostar Bridge is one such example. Built in 1566 by the Ottoman Empire, it was destroyed by Croatian shelling in November 1993.

Soon after the war that ravaged former Yugoslavia, work began to rebuild the bridge, leading to its inauguration in July 2004. It quickly became a symbol of the end of the conflict and the peace that ensued.

Europe: bridges on banknotes

Even the European Union has wanted to celebrate the symbolic value of bridges. With the introduction of the euro as everyday currency, it chose to decorate the banknotes with the design of various bridges. These structures emphasize how a single currency brings people and their countries closer together on the old continent. From the €5 banknote to the one denoting €500, a bridge is used to represent different eras of the history of Europe: from the Classic (€5) to the Roman (€10); from the Gothic (€20) to the Renaissance (€50); from the Baroque to Rococo (€100); from the Industrial Revolution (€200) to contemporary architecture (€500).

The selection of the design for each bridge was done by a team of engineers, architects and art historians who sought to avoid identifying a specific bridge by conceiving structures that were representative of the various ages to underline the role that bridges have in the collective imagination, like an arm that extends itself between distant worlds.

From the past to the future

From the Pons Sublicius in Italy, built in 642 B.C. by the Romans and considered one of the oldest in the world, to the most recent projects, the role of bridges in the history of humanity has been one to bring together what was formerly apart, enabling exchange of every sort.

Bridges have also inspired artists: there’s the bridge of Argenteuil painted by Monet and Van Gogh’s small bridge of Langlois.

The result of this inspiration can also be found in literature. Franz Kafka wrote a story entitled “The Bridge”, which begins with the lines: “I was stiff and cold, I was a bridge, I lay over a ravine.”

The ravine can be nothing other than an abyss, emphasizing the importance that bridges have in uniting two worlds, helping bring wealth and well-being from one region to another, from one community to the another.

Whether it be the seemingly endless serpentine length of the bridge that will link the Peak skyscraper of Hong Kong to the casinos of Macau, or the majestic sweep of suspended bridges, the profound sense of the structure remains the same: the act of bringing people together and breaking down barriers. Just as Pope Francesco said a year ago in remembering the fall of the Berlin Wall: «Never build walls, only bridges.»