In May, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation suggested setting up a Sino-Japanese consortium to build a high-speed railroad in Thailand. If the idea gets off the ground, it would be the first time that Chinese and Japanese companies work together in a third country. A pioneering agreement that would mark the starting point for overcoming an historic rivalry in the region and to clinch an alliance centered on economic development and infrastructure.

The result is a commercial and industrial rivalry for geopolitical control of South East Asia, being fought with the weapons of technological innovation and competitive pricing, and carried out on the battlefield of infrastructure. The players are not just the two countries’ construction giants—also deeply involved are the governments that for years have been awarding public funds to finance these gargantuan works.

This rivalry is now heating up as a multi-billion-dollar spending pie gets divided. The Asian Development Bank calculates that from 2016 to 2030 countries in South East Asia will need to spend $2.8 trillion in infrastructure, or $184 billion annually. Indonesia will need to spend the most, for a total of $1.1 trillion over that period, and it certainly getting a head start. Indonesia is currently the most active infrastructure player, with 250 projects underway; the Philippines have planned investments for $180 billion to build railways, roads and airports; Singapore is doubling its railway network.

A contest being fought $1 billion at a time

Bridging the infrastructure gap is imperative for many of the countries in South East Asia, which on one hand are earmarking significant portions of their gross domestic product to support large infrastructure projects, and on the other hand are looking for international investors who are willing to enter into partnership on the biggest ventures.

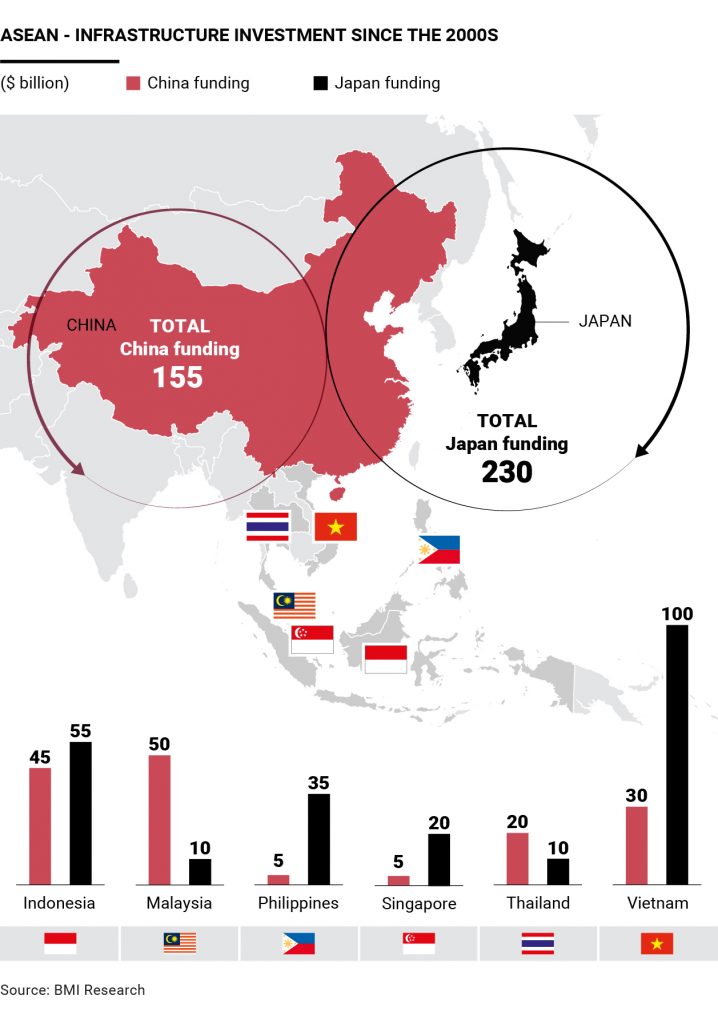

According to BMI Research, since 2000 Japan has financed $230 billion worth of projects in the region (completed or under way), while China has spent $155 billion.

China in recent years has exported its infrastructure products and technology across Asia. And Japan has done the same.

High-speed railways is the sector where this rivalry is the most visible. In 2015 a Japanese company was beaten by a Chinese competitor in a $5 billion tender to build a high-speed train from Jakarta to Bandung, in Indonesia.

Japan’s answer was not long in coming. That very same year, the country of the Rising Sun won a $15 billion “soft loan” to build a high-speed railway in India, between Mumbai and Ahmedabad. The same script was repeated in Thailand, where companies from both countries are active.

It is hand-to-hand combat. While companies take part in important public tenders, governments do their part by deploying all of their available resources.

So while China unveiled the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in December 2015 with $100 billion in funding, Japan replied in May of the same year by inaugurating the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI), with precisely the idea of launching modern and innovative infrastructure projects in South East Asian countries.

For its part, Japan enjoys a longer tradition and historic sector presence in many of these Asian nations. However, this advantage has been eroded in recent years by China with its launch of mega projects like the Belt and Road Initiative. It has closed the gap and now competes for leadership in the region on equal footing with Japan.

A rivalry with old roots

Japan began in investing in large scale infrastructure projects in South East Asia back in the 1970s, thanks to the market penetration of large multinationals which brought jobs and transferred knowhow. That is what happened in some of the most important cities on the continent, like Bangkok and Jakarta. In 2010 this strategy was summed up in the “The Comprehensive Asia Development Plan” written by Japan’s Economic Research Institute and commissioned by the Japanese government. The report outlined how the country’s infrastructure development strategy followed three different guidelines: the East-West Economic Corridor, which runs from Vietnam to Thailand; the Mekong-India Economic Corridor, which links Ho Chi Minh City to Bangkok; and lastly the Maritime ASEAN Economic Corridor, which aims to develop ports connecting Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines.

China, for its part, embarked on its infrastructure development policy in the region much later than Japan. In fact, its first big projects date from the early 2000s. The big push came in 2013, with China President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which includes the Maritime Silk Road and the Silk Road Economic Belt.

The goal of the plan is to boost China’s global trade by building rail and sea links connecting it with South East Asia and with Europe.

From infrastructure to geopolitics

Considering the strategic value of the infrastructure works that have been built or are in the works, the rivalry in this sphere easily extends into the area of geopolitics. Both China and Japan are elbowing each other for more space to grow their sphere of influence among the ASEAN countries, each of them clinching partnerships and commercial accords with one government after another.

Despite their strong rivalry, in recent months both giants have shown signs of interest in finding a common ground to launch shared projects and strategies.