Ten thousand kilometres. How far – or long – is that? In a straight line, it is more than three times the distance between Sydney and Perth – or Melbourne and Darwin for that matter. Or more than two times the width of the Australian continent. Or a third of the circumference of its coastline. Whichever analogy is preferred, it gives a good idea of how many additional transmission lines that the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) calculates are required to support the country’s ambitions to produce all of its electricity with renewable sources by 2050.

The AEMO is an authority on the matter because it manages the largest gas and electricity systems and markets in the country, covering the eastern and southern states of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia.

The “backbone” of Australia’s Energy System

It recently published the latest version of its Integrated System Plan (ISP), which prescribes the best way for Australia to pursue its energy transition. In it, the AEMO says the power grid will need all those thousands of kilometres of transmission lines so it can support the surge of extra power it stands to receive as more wind turbines, solar panels and hydroelectric turbines come online thanks to the billions of Australian dollars being invested in them. Without the lines, all that power to be produced by these renewable resources risk going nowhere. As AEMO’s chief executive, Daniel Westerman, explains it, transmission lines are the “backbone” of the Australia’s energy system: “The transmission network brings electricity where it is needed, when it is needed, and improves the power system’s resilience”.

In a speech made at a recent industry conference, Westerman explained succinctly the need for more transmission lines: “First, electricity demand is growing, in particular as we electrify other parts of the economy, like transport; second, (they are needed) to connect new areas of generation, where strong solar and wind resources exist; and third, for resilience and insurance against unfavorable weather patterns in a system increasingly reliant on variable renewable generation”.

The biggest transformation of the Australia’s Energy System

There is a definite urgency to all of this, since the country must have enough generation, storage and transmission assets installed to substitute what its ageing coal-fired power plants have been producing for decades. If not, it risks blackouts as the last of these dirty plants progressively shut down by 2040. In order to do that, the AEMO says the National Electricity Market (NEM), the interconnected power system that brings electricity to eastern and southern Australia, must almost triple its capacity to supply energy by 2050 in order to meet the expected increase in demand.

Although it has a lot more to do, the country has made good progress: renewables accounted for almost 40 percent of the total electricity delivered through the NEM in 2023. In October of the same year, it reached 72.1 percent. According to the ISP, this energy transition, well underway, is by far the biggest transformation of the National Electricity Market (NEM) since it was formed 25 years ago.

A return on investment

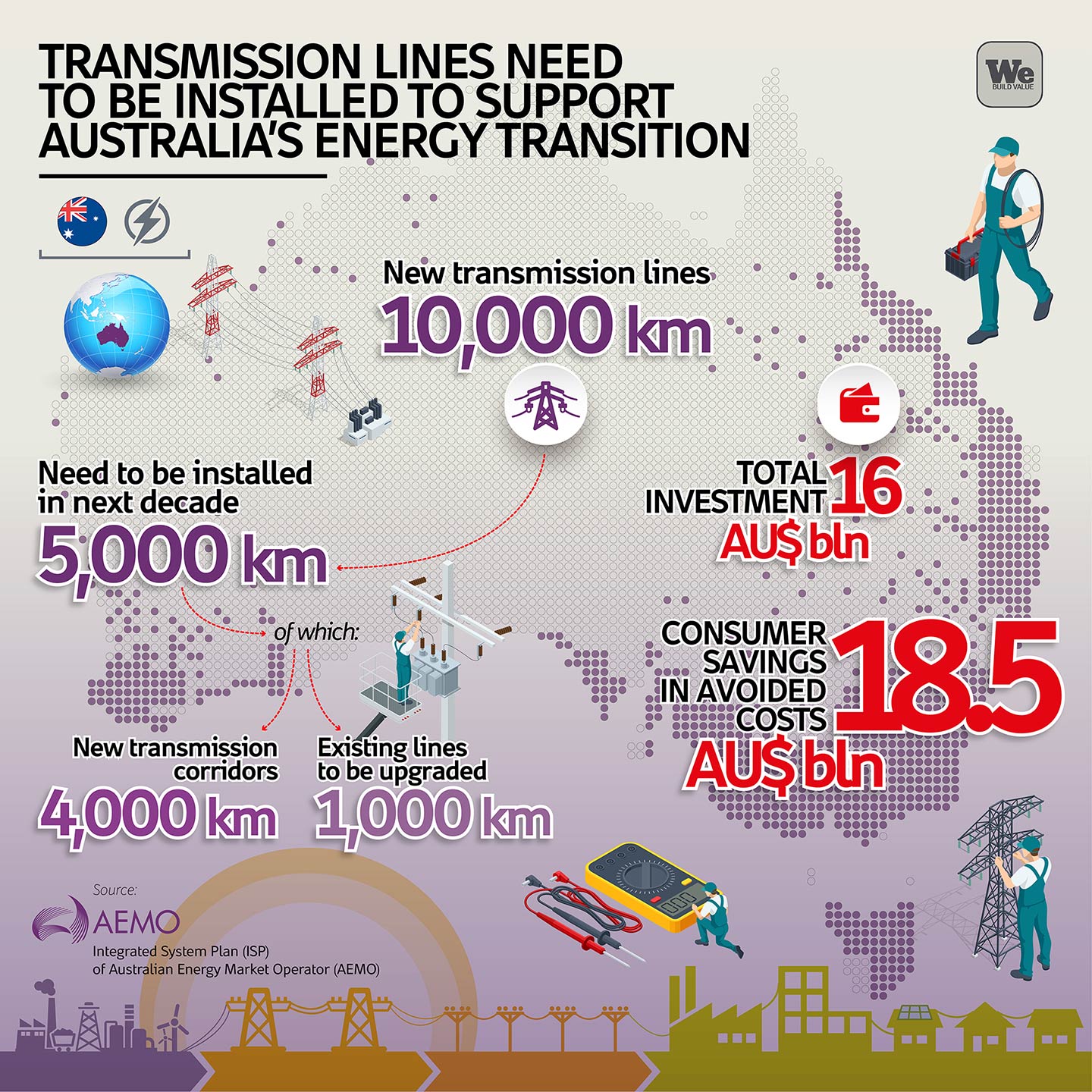

Of the 10,000 kilometers of transmission lines that the AEMO says need to be installed, about 5,000 kilometers must be done in the next decade: about 4,000 kilometers of new transmission corridors and the upgrading of some 1,000 kilometers of lines. As for the $16 billion in costs involved, the “transmission elements would repay their investment costs, save consumers a further $18.5 billion in avoided costs, and deliver emission reductions now valued at $3.3 billion”, says the ISP.

When it comes to installing the lines, it is often done by the same companies that are bringing renewable energy to the power grid. For example, a hydropower project needs not only a dam, turbines and other infrastructure to serve its purpose, but also transmission lines since it is usually located far from the cities where it is to send the electricity that it will produce.

Italy’s Webuild, for instance, oversaw the installation of nearly 400 kilometers of lines to connect projects it built in Ethiopia, including Gibe III, which was the biggest in the country when it went into service in 2016 with an installed capacity of 1,870 MW. In Australia, the Group, along with its local subsidiary Clough, is behind Snowy 2.0, a pumped hydro energy storage scheme that is the largest renewable energy project under construction in the country.

The ability to install transmission lines over long distances can also be demonstrated by having overseen the development of what is known as linear infrastructure. The term literally means anything that is built in a straight line: roads, highways, railways, canals.

For more than a century, Webuild has built more than 14,000 kilometers of railways and metro lines, one of the most recent being the Airport Line in Perth. Previously known as the Forrestfield-Airport Link, it is an 8.5-kilometre rail line that connects the eastern suburbs with the city centre via a stop at the airport. Since trains that run along lines of this type must be electrified, there will always be a connection to substations, which in turn are connected to the power grid.