Taking Seventh Avenue south from Times Square has always been a gamble, a sort of slalom dodging people on crowded sidewalks, store doors that slide open to puff cold air in the summer and hot blasts in the winter, and navigating giant restaurant chains recalling the assembly lines of last century’s factories.

Today’s Manhattan is something different. The Manhattan of Covid-19 now hangs on immunologist Anthony Fauci’s every word, hoping to get the “green light” that can jumpstart life the city.

Today’s city lives in suspended animation. It keeps working — because no one can stop New York City — but with wariness. You can see this wariness as you walk through the narrow streets of Greenwich Village, where instead of small coffee shops with paintings signed by the Rolling Stones, there are now private labs selling Covid tests as if they were doughnuts. Or surfing on Google Maps where the usual icons — Macy’s and Cipriani, Gucci and Saks — are joined by CityMD, where you can get a swab for free.

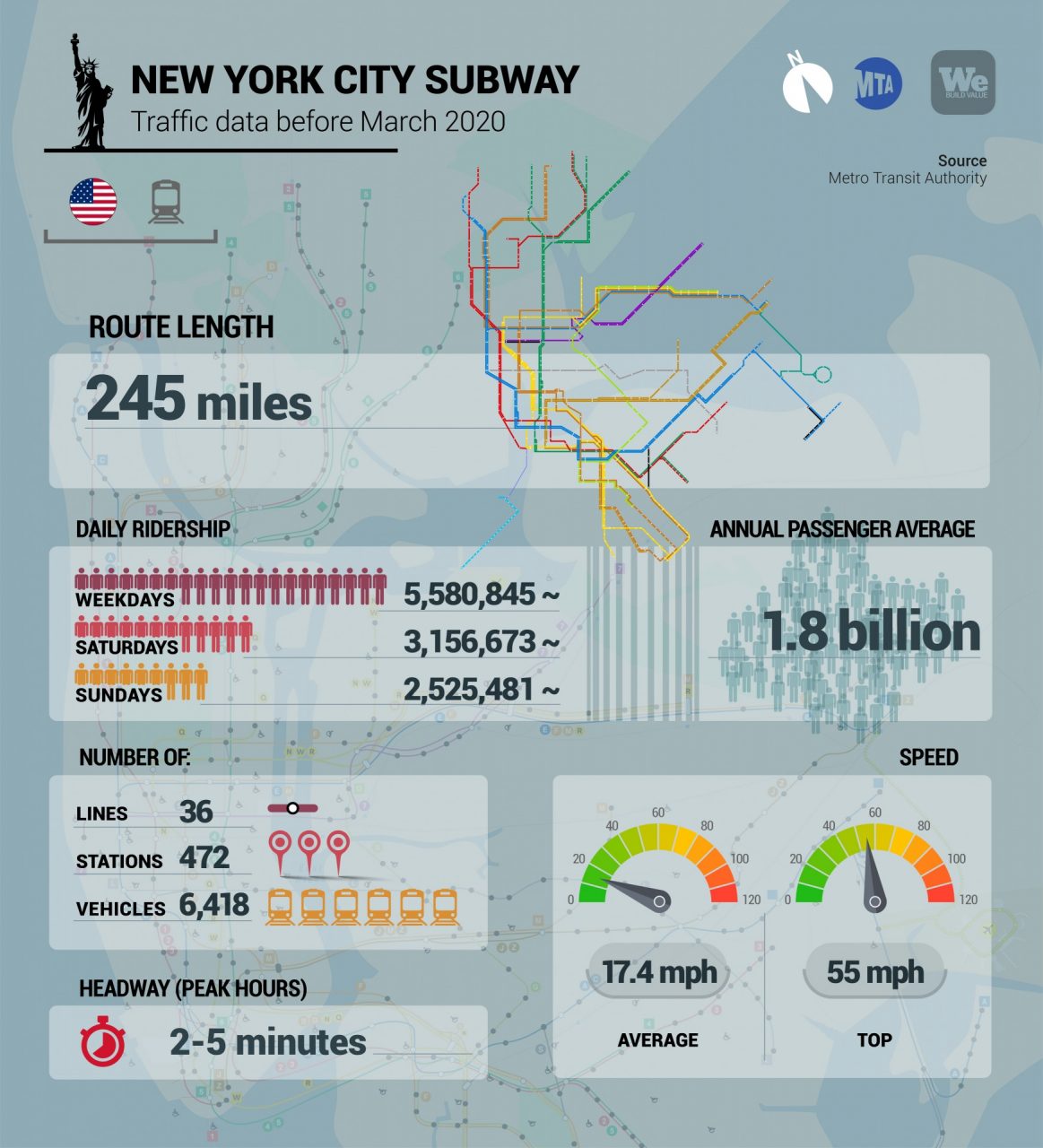

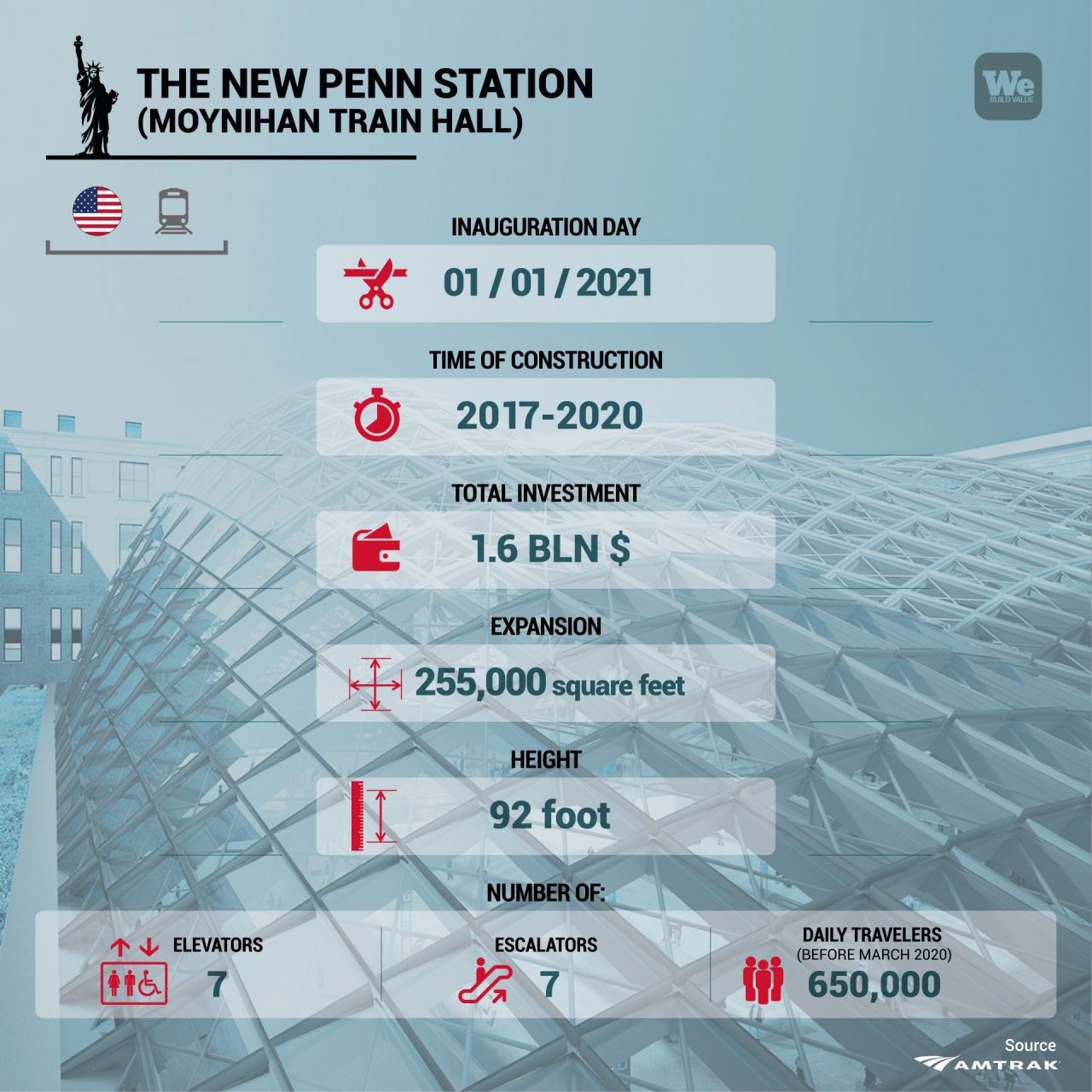

And yet, walking down Seventh Avenue where even the maps of everyday life have been rewritten, something has stayed the same. At Seventh Avenue and 33rd Street is Penn Station. As of January 1, the historic subway and train station, probably the most important public transportation hub in the United States, has been rebaptised with a new name and a new expansion. The year 2021 began with the christening of the Moynihan Train Hall (named after Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan who supported the project 30 years ago). The station has been enlarged to include the old James A. Farley post office, thus increasing the size of this huge rail traffic hub by 50%.