The terrible wildfires that have brought California to its knees – with a dramatic death toll rising every day – is a tragic confirmation that the war on drought being waged by American’s richest state is far from over. These latest wildfires are yet another reminder of the urgent need for infrastructure capable of improving water management, which today is a resource at risk.

For decades, California has been waging a battle (there is no other word for it) against the lack of rain, its chronic water shortage, and the aridity of its land.

According to the US Drought Portal (the government web site that monitors climate conditions across the US in real time) – this plague now affects 23.6 million people, or 63% of California’s population.

The map of the state, elaborated by the US Drought Monitor (USDM) on October 30, shows that 36.9% of its land is affected by a water shortage, above all for agricultural use; 28.6% is affected by moderate drought; and 16.6% is forced to deal with serious drought. In 2.7% of the state, the drought is considered extreme.

The most critical time, naturally, is summer. Last July, 85% of the state was affected by drought. From the eastern zone of Napa Valley to Lake County, from the county of Mendocino to San Luis Obispo on the Mexican border, conditions varied but were nonetheless worrying.

When there is no rain, the land dries up, farmers have no water for their crops, and rationing becomes the norm for daily use in big cities. And this is after the five year drought that just ended.

A battle with no end in sight

In April 2017, California Governor Jerry Brown declared an end to the drought emergency that had beleaguered the state for five years. «This drought emergency is over, but the next drought could be around the corner. Conservation must remain a way of life», Brown said in the official statement that declared an end to the emergency.

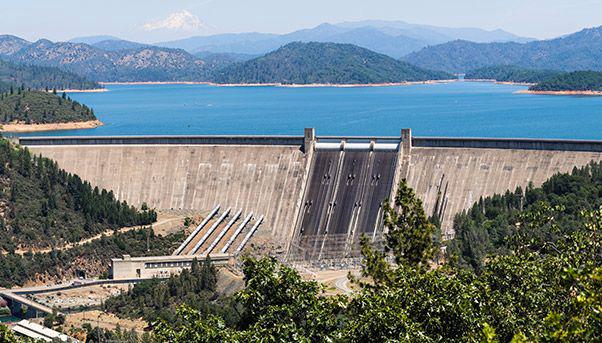

Even as heavy rains blessed many areas of the state during the spring of 2017, water conservation moved to center stage as a clear and crucial theme. Existing water facilities must be modernized and new ones must be built that are capable of storing rainfall and using it in certain periods of the year where and when it is needed the most.

That is why – despite the end of the emergency – acting Governor Brown has obliged city governments to submit constant updates on how water is being used and the measures being put in place to fight water shortage. Water conservation is currently the most widespread method of fighting drought, because it involves everyone from city governments to companies, and even citizens, who are committed to reducing consumption at home. The goal is to ensure that water reservoirs do not fall below 20% of their capacity. This is imperative to prevent water shortages from doing even more damage to California’s economy.

The cost of drought

The cost of drought is very high. And everyone pays, from the state to companies, from local administrations to city dwellers.

In the last five years, the agriculture sector has lost an annual average of $1.5-$1.8 billion in revenue, consumed in part for a lack of water and in part because of the devastating impact of fires.

Wildfires a common feature of California’s hot summers. There were 2,600 fires in the summer of 2018. Fires have a dramatic impact on the economy as a whole. Fed by winds that can reach speeds of 60 kilometers per hour, fires cause severe economic damage because they also affect tourism, real estate and overall employment. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection calculated that wildfires have caused nearly $3 billion in damage since the start of this year, burning nearly 1.5 million acres.

In terms of employment, the Center for Watershed Sciences calculated that 21,000 people lost their jobs in 2015 due to water shortages and its impact on the economy. California’s inhabitants have learned to deal with it.

Defeating an historic enemy

California’s draught problem is not a recent one. The California Department of Water Resources retraces the state’s difficult relationship with water, recalling that the first and most devastating wave of draught took place from 1920 to 1930. This longest period of drought in the past 100 years was followed by other moments of great anxiety, like the years 1976-1977, 1987-1992, 2007-2009 and finally the most recent drought that took place from 2013 to 2017 with impacts that are still being felt today.

Tackling this problem means confronting this historic enemy, which can be defeated only by coming up with new solutions and taking advantage of new technology. Innovative projects like the hydraulic tunnel beneath Lake Mead bringing drinking water to Las Vegas from the nation’s largest artificial lake, or the eight projects that call for the construction of four dams and for underground hydraulic facilities go in this direction. Governor Brown has given a big push to solving the problem by announcing $2.5 billion in funding to deal with the water crisis. This is an important step to improve existing water management and to continue the emphasis on water conservation, which is the only way to prevent California from being crushed in the jaws of drought yet again.