At the bus stop between 23rd Street and Second Avenue in New York City, one of the advertising boards flashes the latest publicity campaign by United Airlines: a taunt to travellers who think that going to the John F. Kennedy International Airport is a quick and easy ride.

The six-terminal airport named after one of the most famous U.S. presidents might have train and metro connections to the city but the campaign prefers to focus on the roads. That is because going by car between the airport and the city is a true odyssey: the Van Wyck Expressway that links the Queens neighbourhood with the airport and leads traffic away from Manhattan is perennially congested.

Meanwhile, the Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey, from where United Airlines flies, is farther away from the city on the other side of the Hudson River but it still acts as a second airport to New York because it can be easier to reach. It is for this reason that the airline plays on the troubles of those who face a long hike to JFK.

Roads are the Achilles’ Heel of America. They are either old, inadequate or in poor shape. More of them are needed – and built better too. Nevertheless, roads eat up half of the public spending on the country’s infrastructure.

Transportation infrastructure investment in the United States

According to the July 2017 report “Economic Impact of Infrastructure Investment” by macroeconomic analyst Jeffrey M. Stupak for the Congressional Research Service (the internal research body of the U.S. Congress), about half of the $126 billion that Congress sets aside for infrastructure in a given year (federal transfers to local authorities) goes to projects in the transport sector.

So why is it that infrastructure in the United States is failing when it was such an issue during the presidential election that brought Donald Trump all the way to the White House?

Probably because the country has been cutting costs and saving for decades even though the budget still seems big. In the 1960s, the report says, the United States invested the equivalent of 4% of its gross domestic product (GDP) in public works outside of defense. Today, the rate stands at 2.6%. It is true that the country’s GDP is greater today than it was 50 years ago but the figure shows how spending has declined in relative terms.

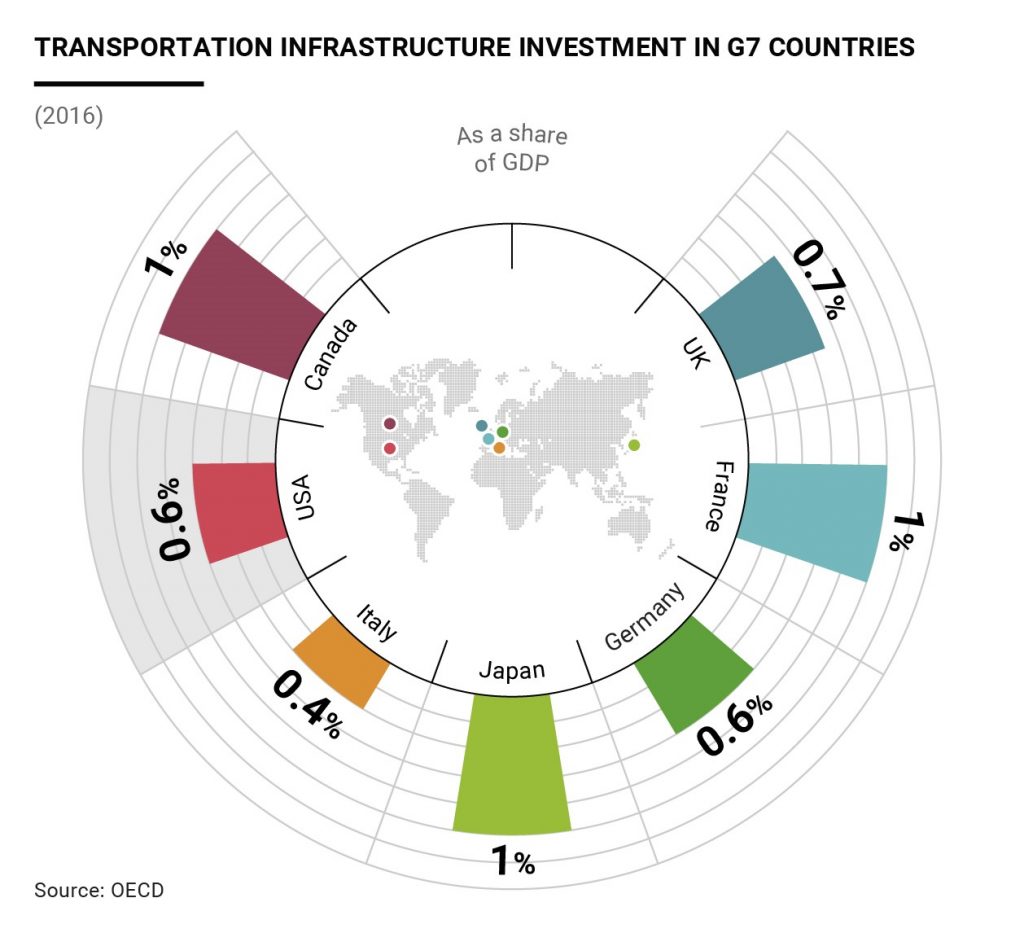

Since the 1960s, investment in the transport sector has fallen to a minimum of 1.55%. The trend changed course in early 2000, but after reaching a peak of 2% in 2009, it returned to minimum levels of 1.5% again. This has relegated the United States to the last spot among G7 countries . Indeed, with average expenditure in transport of 0.6% of GDP, it runs in third last place , according to figures from the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Only Italy and Germany are the same or worse , while the average among OECD countries is 0.8%. It is not a record to bring proudly to Washington, D.C., because infrastructure is what is needed to make economies grow in any country.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) calculates that a rise in public spending equal to 1% of GDP can lead to a 2% drop in unemployment in four years – but only when it is financed by debt.

Stupak, the author of the report, goes further by calculating the impact of infrastructure on an economy in the medium to long term. What he found out was that public spending works in the long term rather than the short : 1% more spending can bring a GDP rise of 0.083% or $12.7 billion in the short term, while in the long term it rises to nearly $19 billion or 0.12%. So it is better if the spending is done with debt because it can have a multiplier effect. If public spending is done otherwise – at zero cost to the balance sheet – resources are inevitably detracted from somewhere else. This results in hampering the rise in aggregate demand. Simply put: you take away from one place to give to another. This is why building bridges and railways with debt has greater resonance: the Congressional Budget Office calculates that a $100 billion rise in deficit spending would lead to a $20 billion rise in GDP in the short term.

Coupled with U.S. President Donald Trump’s proposal to increase investment in infrastructure, the report is an urgent call for more public works that can, in turn, contribute to further economic growth.