More than any other continent, Africa is struggling with the high cost of inadequate – if not the lack of – infrastructure. This enormous problem prevents countries from going very far along the road to development.

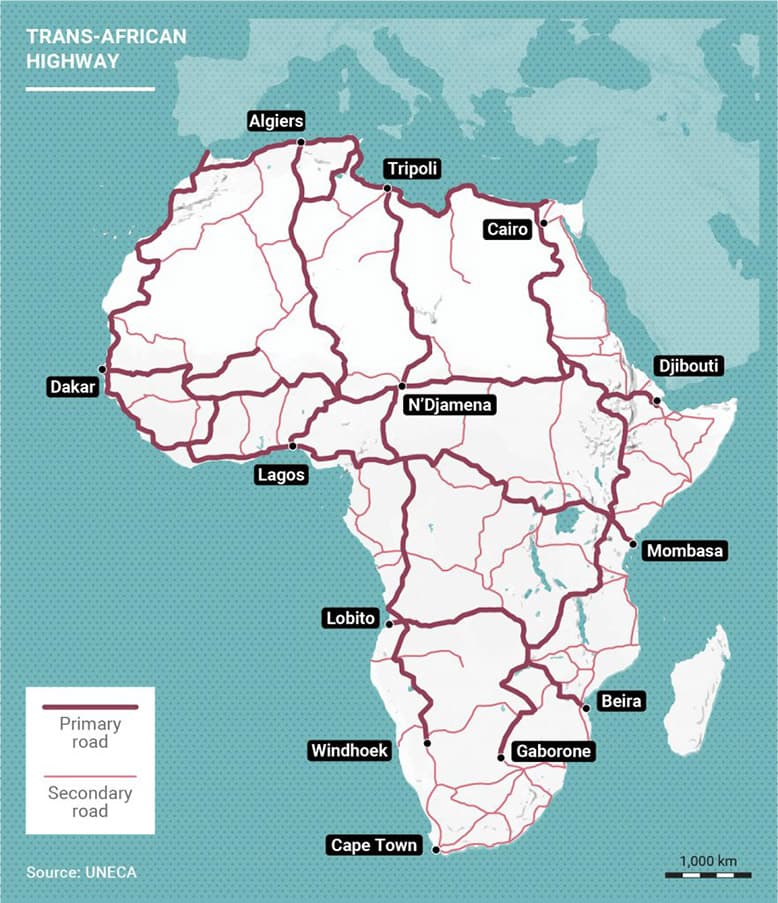

In addition to incomplete projects like the Trans-African Highway, Africa suffers from small obstacles that often seem insurmountable.

Crossing a border, for example, can be a complicated affair.

On the Congo River, the cost of a return journey across its narrow waters separating Brazzaville and Kinshasa would be equal to a $1,200 toll for the use of the bridge between Oakland and San Francisco.

The implications that this has for trade on the continent are obvious.

Infrastructure in Africa is so poor and lacking that it is a major impediment to development, according to “Aid for Trade at a Glance 2017”, a report compiled by multinational organizations including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

But the continent might be taking a turn for the better as it prepares for the introduction at the end of the year of a Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) covering the entire African Union, the most extensive market in the world.

The simplification of border controls and the drop in duties and other costs like tolls are seen giving a 52% boost to trade on the continent to $35 billion in five years, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

This expected surge in economic activity is also seen encouraging investments in roads, railways and other infrastructure to make it easier for countries to deal with each other. One of these pieces of infrastructure that will likely receive greater attention is the Trans-African Highway, the largest – although unfinished – project the continent has harbored for nearly half a century.

But it all risks coming to naught if investment in the Highway and other major projects do not materialize.

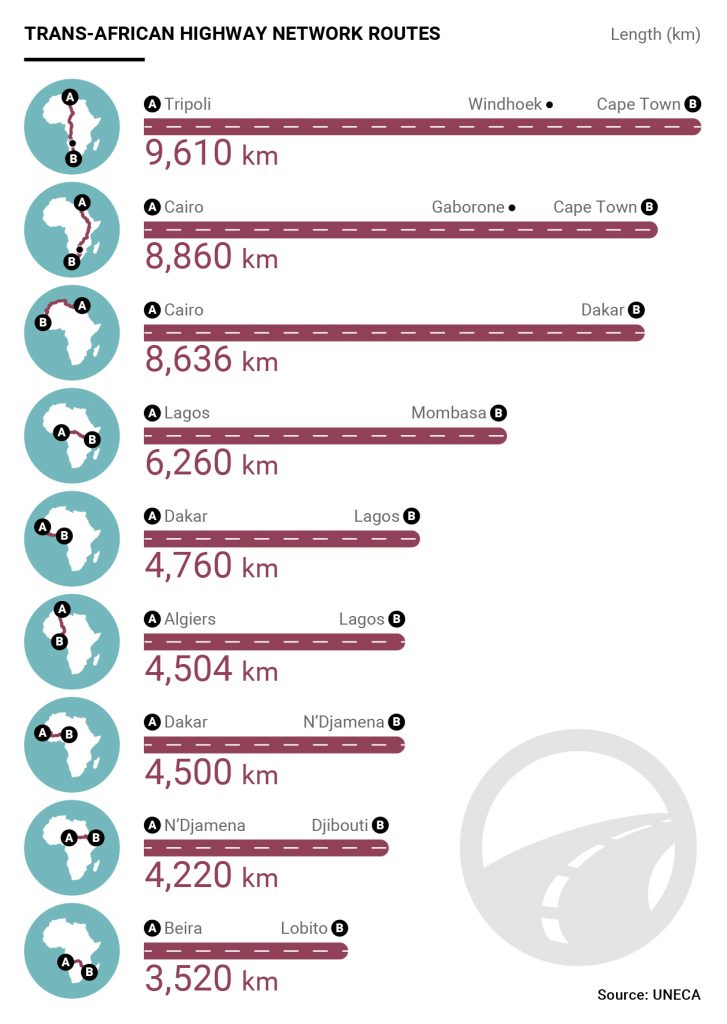

Trans-African Highway: Nine Highways under Construction

Launched in 1971 by UNECA, it is actually a network of nine highways whose envisioned connections among one another would cover a combined total of 60,000 kilometres across the continent. One of these planned highways would stretch 8,000 kilometres between Cairo and Dakar; another for 8,000 kilometres between Cairo and Cape Town; a third for 6,000 kilometres between Lagos and Mombasa; and a fourth for 4,700 kilometres between Dakar and Lagos. But only one has been completed so far: the Trans-Sahelian Highway, which runs 4,500 kilometres between Dakar in Senegal and N’Djamena in Chad.

Although the others are only half finished, countries are progressively opening them section by section. The Africa Development Bank, one of the project’s financial backers, cites conflict and climatic conditions as reasons for the slow progress, especially in countries like Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Some highway sections that had been built lie damaged as a result.

The cost of the old infrastructure in Africa

Although the CFTA is to come into being in a matter of months, its benefits may prove elusive to many countries in light of the delays in investing in infrastructure to make doing business cheaper and quicker.

Consulting firm KPMG estimates the cost of transportation in Africa is on average 50-175% higher than other parts of the world as a result of poor infrastructure.

Improving land transportation is not the only imperative, however. Bureaucracy is also proving to be an obstacle to greater trade.

The “Aid for Trade at a Glance 2017” report says transport companies in some countries have to handle some 1,600 documents such as permits and licences just to have a single truck cross a border.

Poor roads and other infrastructure are nevertheless the fulcrum of the problem. A retailer in South Africa, for example, complains about how at least one of its trucks arrives late to its destination every day because of bad roads, costing it $500 a trip.

Interestingly, the most recent efforts to overcome the problem have manifested themselves on rails rather than roads.

Transport that works

But there are examples of improving efficiency as a new vision takes shape.

One of them is the recently opened lined between Ethiopia and Djibouti. Built at a cost of $4.2 billion, the first electric train service on the continent is expected to make a dramatic impact on trade. Each train can carry loads equal to 200 trucks, and it does the 750-kilometre route in 12 hours instead of the three days that it takes by road.

Another big project is the $13.8 billion East African Rail Master Plan, a proposal to rejuvenate lines among countries like Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan and Ethiopia. The first section was inaugurated in June, covering Nairobi and Mombasa.