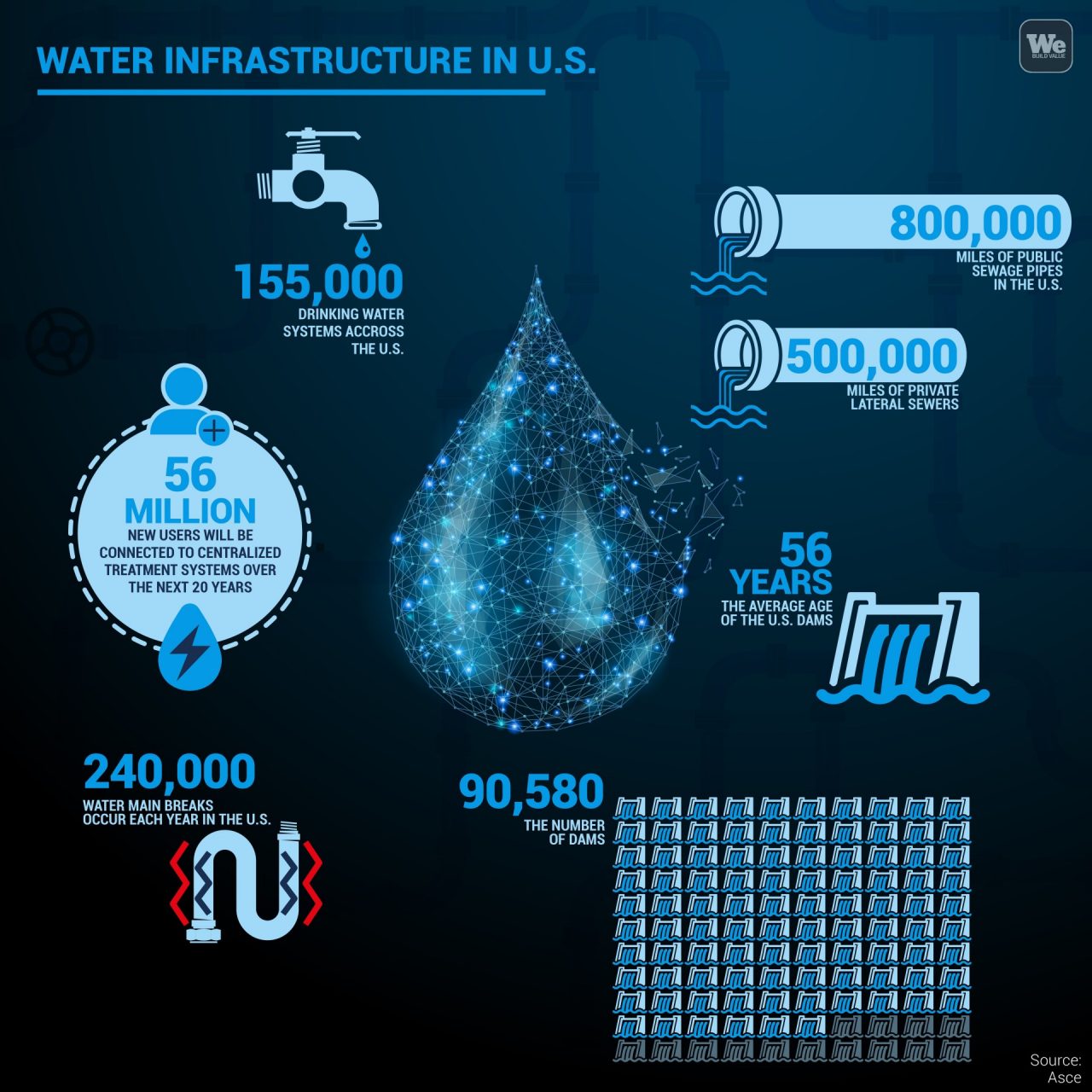

Water is a precious commodity. The infrastructure to safeguard it, keep it clean and drinkable, transport it and transform it into energy is indispensable. To address the need to modernise or replace existing water systems in the United States, the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works (EPW) has just passed the America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2020 (AWIA) bill, which is expected to be voted into law by Congress before the end of the year.

This program earmarks $17 billion in federal funds to assist with the deepening of ports, and address concerns related to inland waterways and floodwaters across the country. Some states, such as Texas, have already had their spending plans authorized in the bill. AWIA, for the first time, introduces new mechanisms to cut bureaucratic red tape.

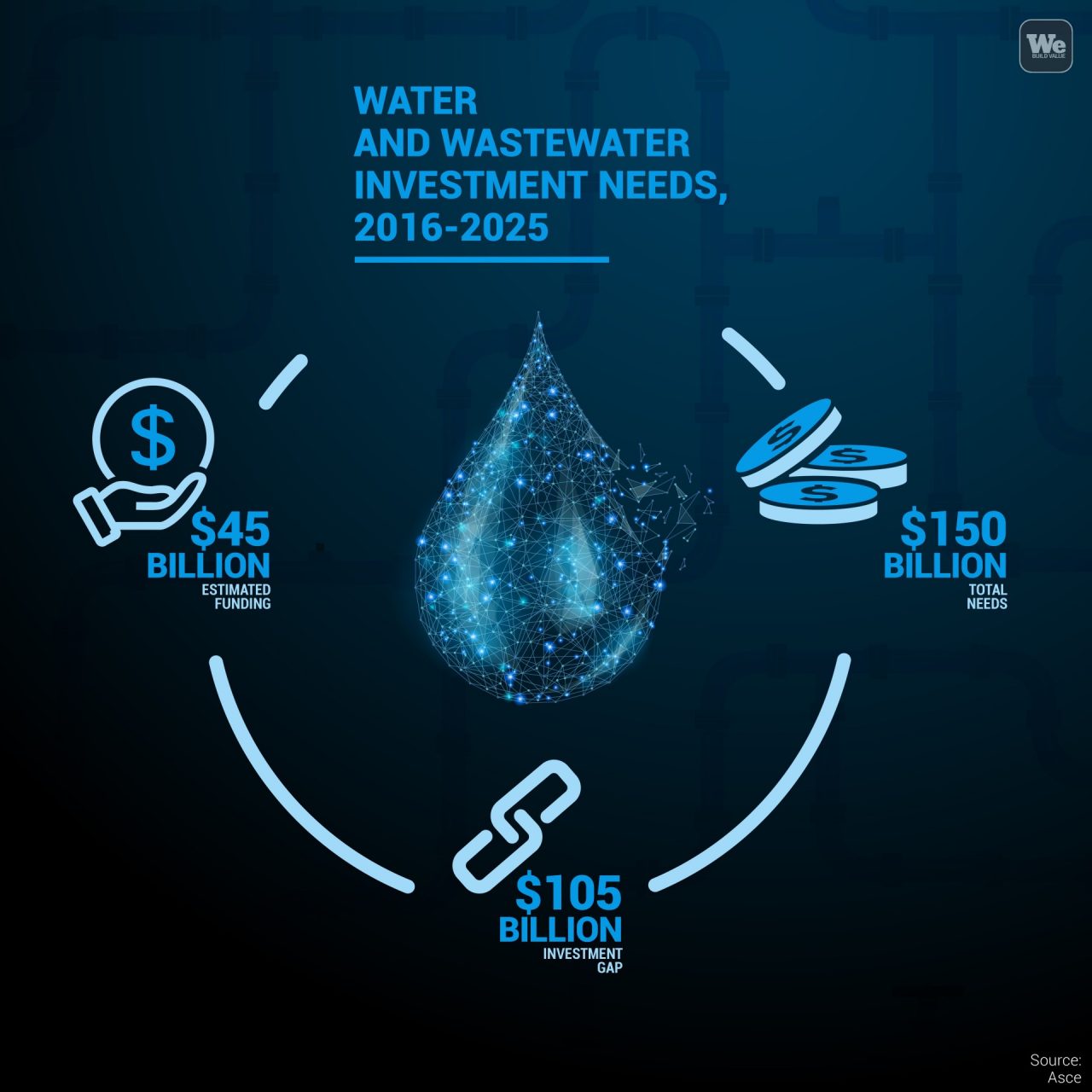

The legislative programme also includes refunding for the 2014 Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA), a federal loan and guarantee program that aims to accelerate investment in the nation’s water infrastructure by providing long-term, low-cost supplemental loans for regionally and nationally significant projects.

In 2019 it received $50 million in new funding each year until 2024, plus $5 million for new loans to state infrastructure financing authorities, with the aim of improving water and wastewater infrastructure. Moreover, another $2.5 billion in new funds will be spent to support the Drinking Water Infrastructure Act of 2020, amending and improving the 1974 the Safe Drinking Water Act to enable certain communities to cope with the lack of drinking water.