The story of Italy’s water emergency can be told by a simple photo of the Po River taken by a satellite in recent days. Seen from above, the country’s longest river — which flows from the Cottian Alps between Italy and France and into the Adriatic Sea carrying an average of 1,540 cubic meters of water per second — resembles a stream. Dried up, shrunken, in some places as gray as the sand that now chokes it. All around, the fertile farmland of the Po Valley has taken on a yellowish color, the color of the sun that burns the land and makes it dry, unable to produce fruits and vegetables.

The image of the Po is an image of the drought that is also affecting the rest of Italy, a country naturally rich in water resources. Italy is a victim of climate change, and is unprepared to manage the impacts because of delays in building an infrastructure capable of handling this crisis. According to Coldiretti, the association representing Italian farmers, the lack of water threatens to ruin 30% of national agricultural production. In the specific case of the Po, the Basin Authority for now has not stopped farms from using the river’s water for irrigation, but has reduced withdrawals for agricultural use by 20% of available water.

To cope with the water emergency, the Webuild Group, one of the world leaders in the hydro sector, has just launched the “Water for Life” project, which will soon be presented to the Italian government and local authorities, calling for investments in the construction of desalinators, plants capable of producing drinking water directly from the sea.

"Water for life," Webuild's plan to protect Italy from drought.

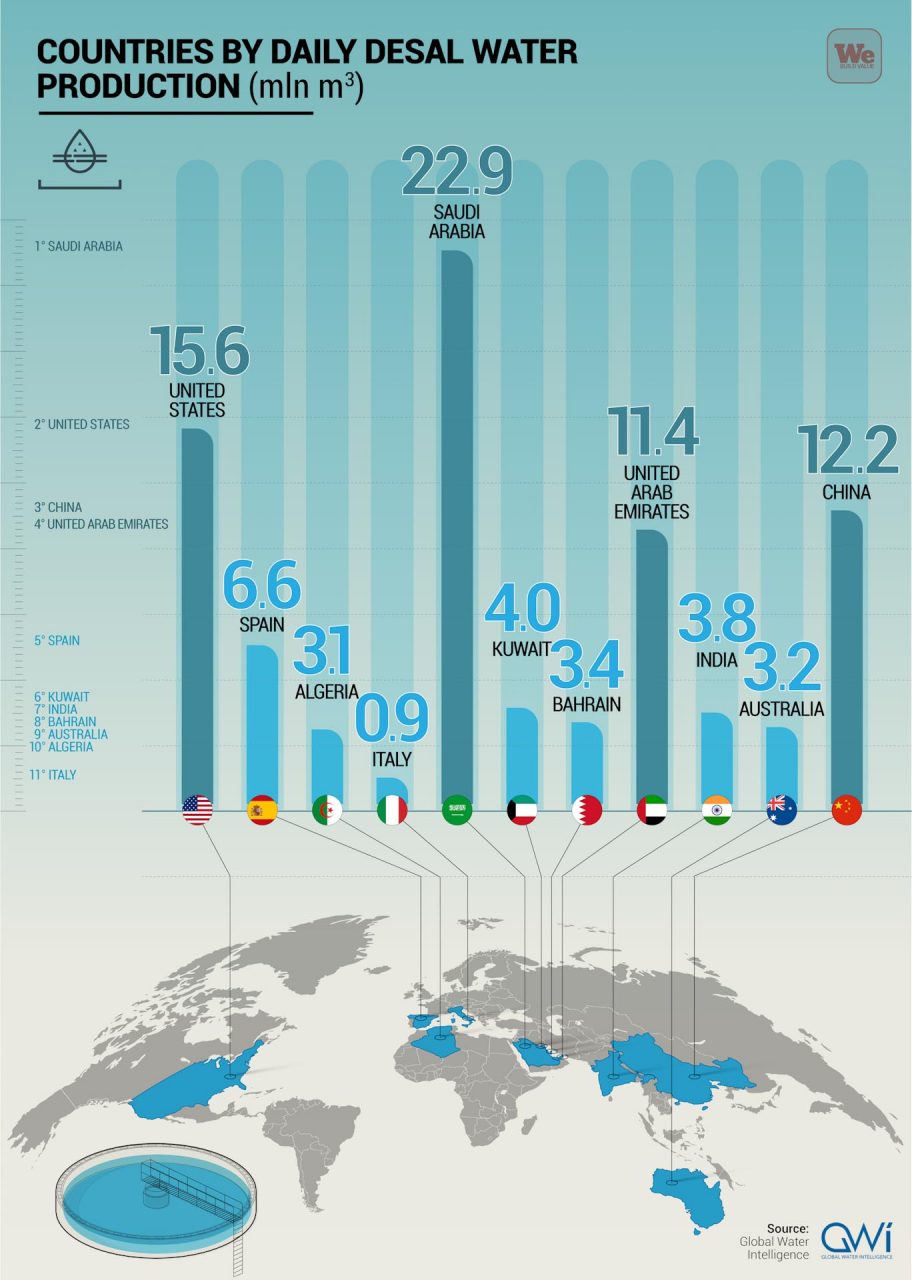

Desalination is a technology with a proven track record in many areas of the world, starting with the Middle East, where water has historically been a rare commodity. Webuild, through its Fisia Italimpianti subsidiary, is one of the leaders in this technology and operates plants in several different parts of the world that transform seawater into drinking water.

The Italian government could also adopt this technology as well, thus solving a crisis that affects both the dry southern regions but also the agricultural regions in the north.

“Counting on the Group’s enormous worldwide experience on water including the desalination technique,” said Pietro Salini, CEO of Webuild, “we want to promote a project that will allow the country to solve this increasingly serious endemic problem. Our subsidiary Fisia has already built most of the desalination plants in operation in the Middle East, making life possible in desert cities like Abu Dhabi or in water-intensive cities like Dubai. Water shortage in Italy is a historical phenomenon and not just a momentary one related to climate change. Therefore, the country must take immediate and structural steps to solve the water crisis once and for all, including by spending the EU-funded Covid recovery National Recovery and Resilience Plan resources.”

Italy today has a desalinated water production of just 4% of total consumption, compared to 56% in Spain or 26% in Australia, despite the fact that the country is a peninsula surrounded by the sea. Investing in this technology could provide an answer to the issue of the water crisis gripping the country, an answer that can also come by allocating National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) funds to these projects.

A role for the NRRP in combating drought

Faced with images of the Po River running dry, many observers are looking to the NRRP, the National Recovery and Resilience Plan that allocates economic resources to deal with strategic issues such as water supply.

Lombardy Governor Attilio Fontana, one of the regions that depend on the Po River, spoke up about the issue. “We need to look ahead by making structural solutions,” Fontana said in recent days, “which are necessary and cannot be put off. We will perhaps have to spend the funds provided by the NRRP.”

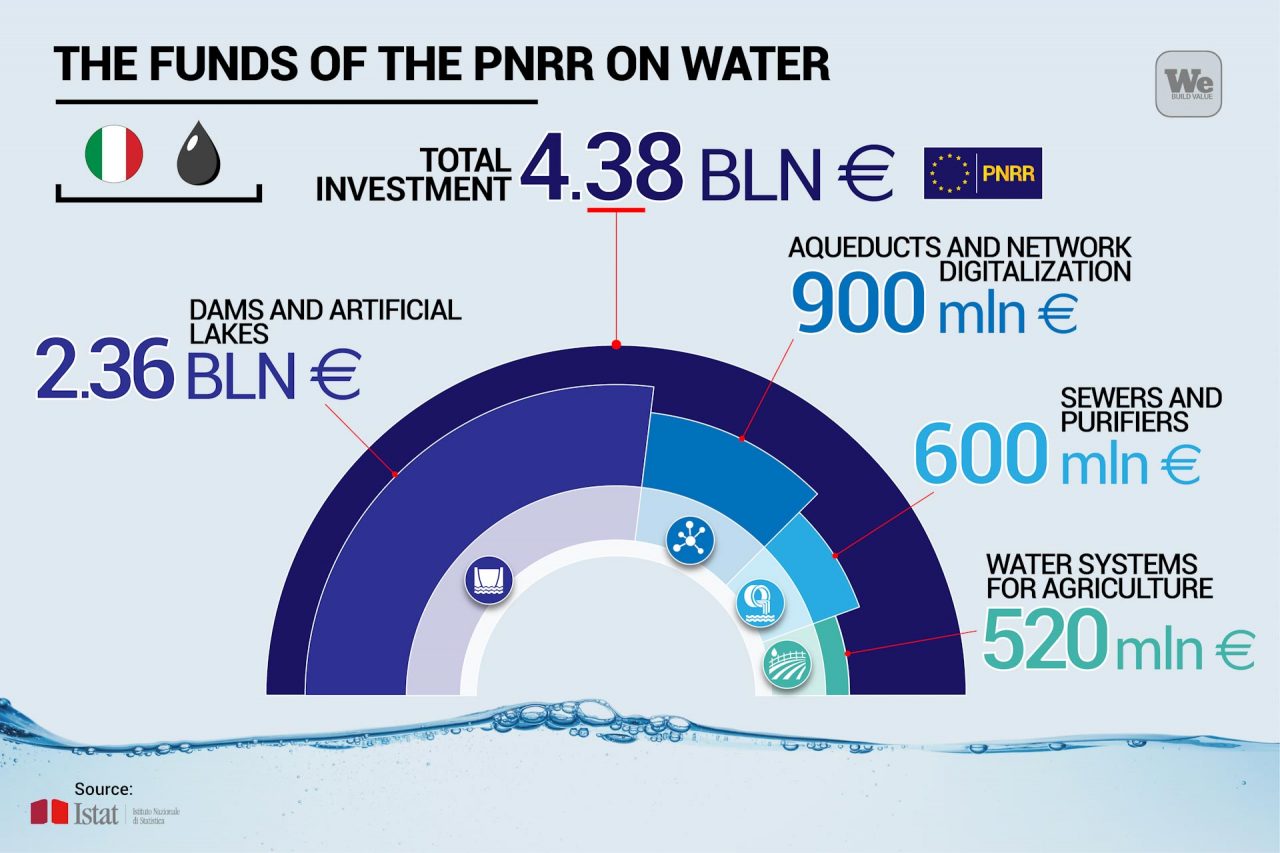

The NRRP funds, however, at least those earmarked for water management, do not seem sufficient to cope with the current emergency. To date, the Plan has allocated €4.38 billion ($4.58 billion) for “sustainable management of water resources” and for “protection and enhancement of land and water resources.” The majority share of these funds (€2.36 billion, or $2.47 billion) is destined for primary water infrastructure for the security of water supply: dams, reservoirs, and connections between aqueducts; €520 million ($544 million) is earmarked for better use of water in agriculture; €900 million ($942 million) for aqueducts; and €600 million ($628 million) for sewers and purifiers.

In reality, according to an analysis conducted by ARERA (the Regulatory Authority for Energy Networks and Environment), this total allocation is inadequate to meet the country’s needs. Overall, the report indicates a total need of €10 billion ($10.4 billion) which should be allocated mainly to projects to reduce if not completely eliminate water losses, thereby improving water quality. The main issue regarding infrastructure is maintenance, because Italy needs structural fixes to its network as soon as possible.

Getting the national water network back on track: here’s the top priority

Coping with the emergency requires a series of infrastructure investments to be carried out in the short- and medium-term, starting first and foremost with the maintenance of the national water supply network.

According to the latest report in 2021 by Istat, the National Institute of Statistics, for every 100 litres of water that travels through Italian aqueducts, 42 are lost. Only by recovering water losses, Istat further calculates, would it be possible to collect enough water to meet the annual needs of 44 million people. As of today, in fact, 9.4% of Italian households complain of irregularities in water service.

New infrastructure, therefore, and massive maintenance work on existing pipelines: this is the only way to cope with the effects of the sad record of zero significant rainfall in the last 180 days. A record that is updated by the hour.