The Klamath river is born in central-southern Oregon, makes its way through the Cascade Range mountains, and flows for 414 kms (257 miles) to the Pacific Ocean, through northern California, which considers it the state’s second river by water flow after the Sacramento. Along its central section, this spring work has begun to remove the dams and restore the river’s habitat, the largest project of this kind in the history of the United States.

The $450 million project, approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) after decades of environmental litigation, comprises the dismantling of four dams, starting with Copco 2, which should be removed this fall, followed by three other dams, Copco 1, Iron Gate and JC Boyle, by the end of 2024. The four dams make up the Lower Klamath Hydropower Project, in California’s Siskiyou county and Klamath County in Oregon. They are owned by PacifiCorp, an electric company owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

Klamath river dams removal: a long journey begun in 2016

A 2016 agreement between PacifiCorp, the Yurok and Karuk tribes, the governors of Oregon and California, and FERC, led to the 2021 transfer of the dams and related infrastructure to the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), a non-profit tasked with the removal of the dams and the restoration of the river’s ecosystem. The deal was aided by the fact that the dams produced very little power and were running at a loss. On March 10, 2023, work began on the access roads, the bridges and the embankments to control the water flow and the discharge of the sediments accumulated in the dams’ basins.

In preparation for this historical removal, the local tribes have been gathering since 2019 enormous amounts of seeds of local plants that will be used to stabilize the sediments. Once the dams are removed, 400 miles of ecological and fish habitat, including the main section of the Klamath and its tributaries, will be restored. The greatest dam demolition ever carried out in the US will also become the most important revegetation and fish restoration project in the country.

Old dams make way for salmon

The Klamath operation comes in the wake of a similar one on the Elwha river in Washington, not far from Seattle. Today the river flows uninterrupted from the snows of the Olympic National Park to the Juan de Fuca strait in the Pacific Ocean. But for about a century, this 72 kms (45 miles) river was blocked by two dams, the Elwha, 32 meters high (105 feet) and the Glines Canyon dam, 64 meters high (210 feet). These barriers impeded salmon migration, destabilizing the communities that depended on them.

And it is the return of the salmon that is cheered the most by the communities along the Klamath river, once the third most important river on the West Coast for salmon spawning. Over the years, the number of fish swimming up river has drastically dropped, due to the dams and the toxicity of the sediments in their basins. The removal of the four dams and the cleanup of the river are a fundamental step for the fish supply of the entire Northwestern US, from the Klamath estuary to Alaska, home of the Chinook Salmon, also known as King Salmon, which in the Klamath’s waters is considered as precious a resource as the gold deposits that caused the gold rush of 1850 and lasted a century.

The modernity of the dams is a central element of their efficiency, as demonstrated by the large projects of Webuild: the large GERD dam in Ethiopia and the Rogun dam in Tajikistan, one of the largest dam in the world.

The priority: maintaining and renewing the great water infrastructure of the US

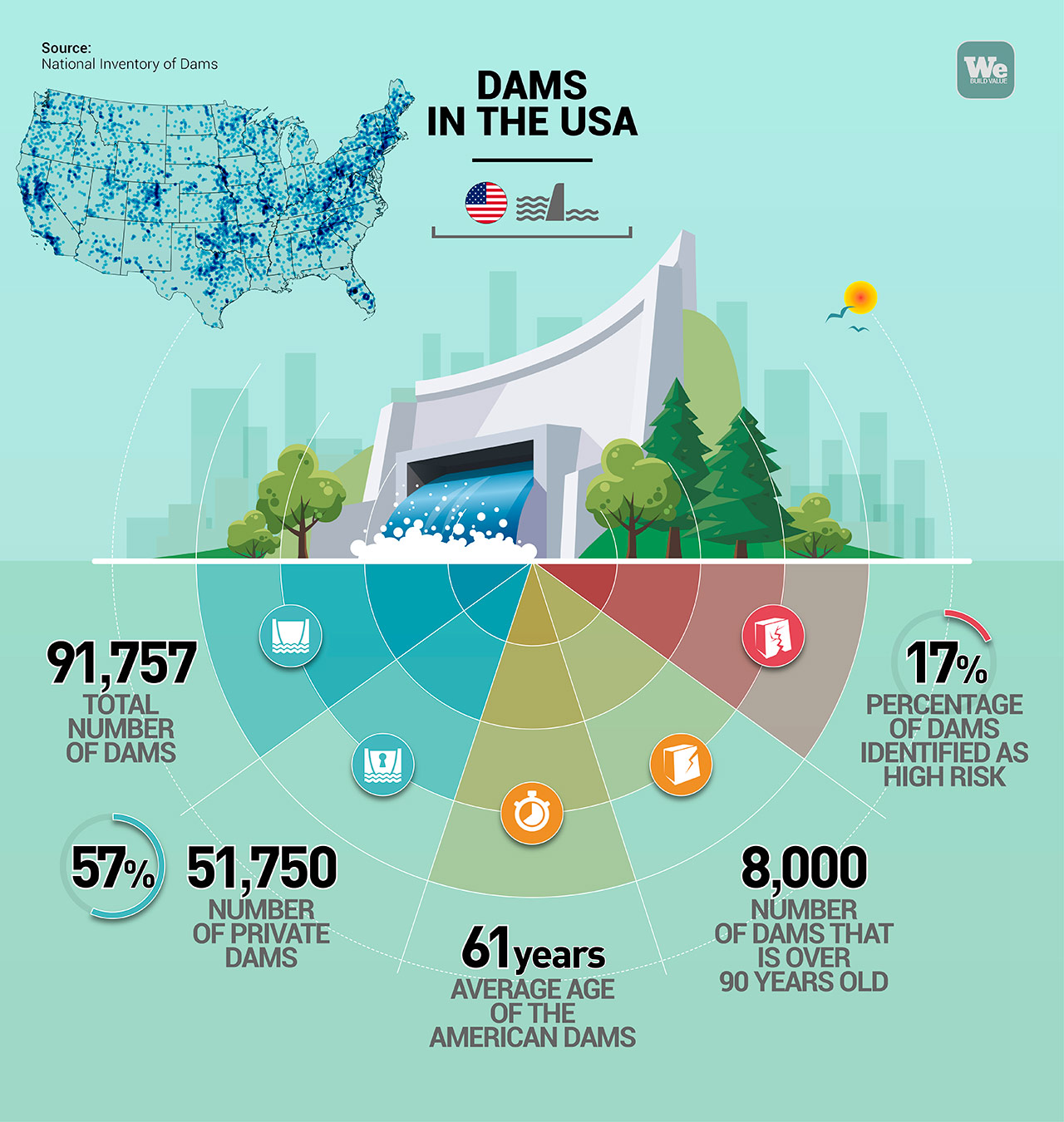

Water infrastructure is one of the most urgent issues in the Unites States, which counts 91,757 dams according National Inventory of Dams (NID), part of the US Army Corps of Engineers. Of these, 51,570, or 56.4%, are private, 20% are owned by local authorities, 4.7% are federally owned, 4.8% are state owned, and 4.2% are owned by public utilities. The ownership of the remaining 9,000 is in a gray area. The dams have an average age of 61 years old, though some are older than 90. Overall, some 17% are classified as high risk. According to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, 3%, or 2,750 are hydroelectric, while 20% are used for flood control.

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) in 2021 estimated that $20 billion are needed just to fix the most obsolete, high risk dams. Investments in this area fail to materialize because of the diverging views on their environmental impact, which led to a freeze on new dams in the 90s. US administrations tend to focus exclusively on minimizing the risks from very old dams or dams that do not meet current standards, which vary between the Federal government and State authorities in terms of management, inspection, safety, maintenance, emergency plans and environmental impact.

According to the American Rivers association, which aims to protect the nation’s rivers, 2,025 dams have been removed nation wide since 1912, 65 of which in 2022.