The Lacey M. Murrow Memorial Bridge, with its 6,620 feet in length (2 km), is the second longest floating bridge in the world. It is a significant artery in the traffic of Seattle, in the state of Washington, which also includes the first and four out of five of the largest such crossings. The Murrow Bridge, named after the director of the Department of Transportation at the time, was opened in 1940 and, while considered a landmark of Seattle, it does not stand out among the most interesting American infrastructure, nor among those with the highest degree of safety. In fact, the bridge, which supports Interstate I-90, a key road artery in the area, has undergone a series of maintenance works over the years and in 1990 it sank due to a storm and human errors during an intervention to improve its stability and remove pedestrian walkways.

Today, 83 years after its inauguration and 33 years after that incident, with no casualties as it was closed to traffic for repairs, the Lacey M. Murrow Memorial Bridge is once again making headlines as it has been included in the list of spans at risk or in poor condition by the American Road & Transportation Builders Association (ARTBA), whose report has just been published.

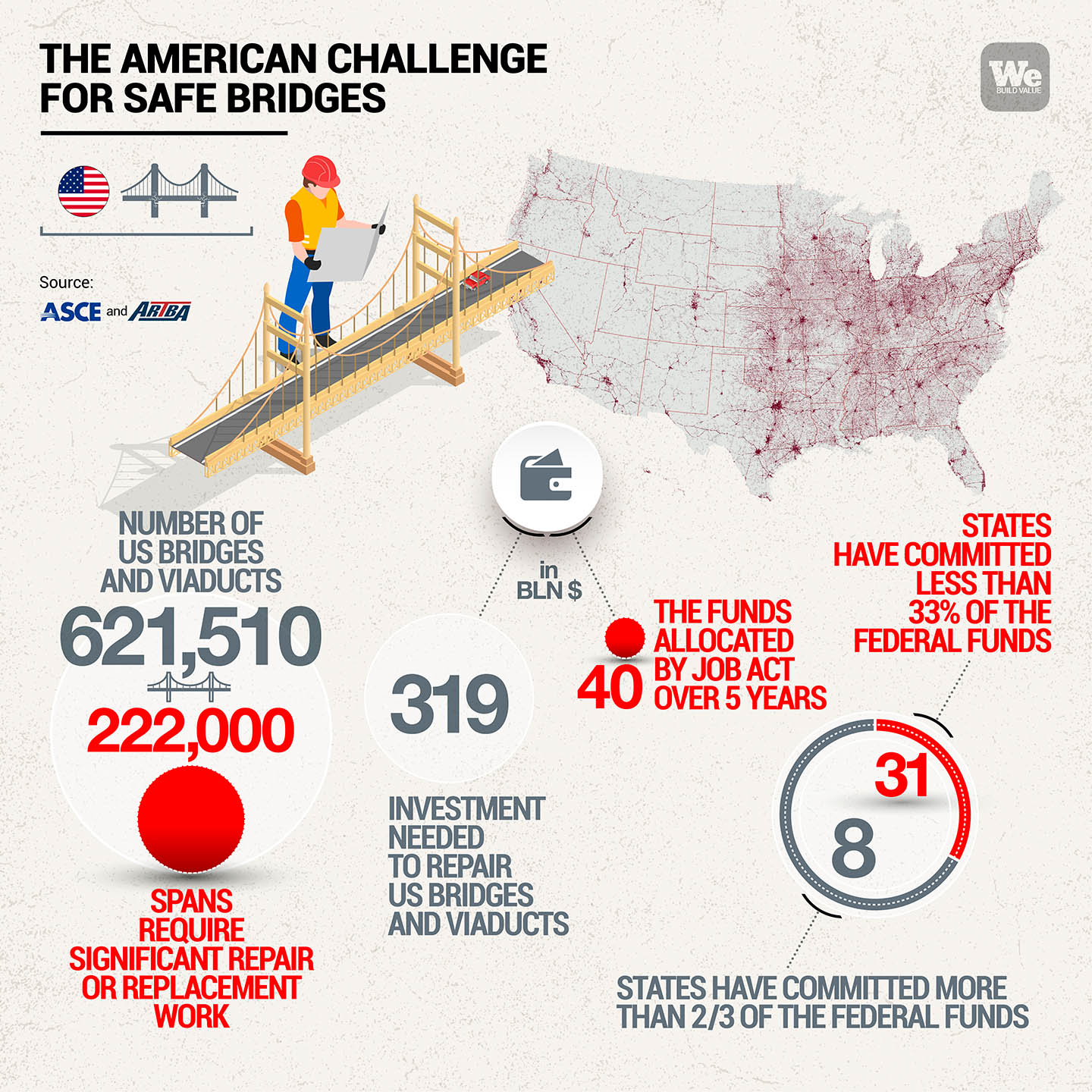

According to the document, which is based on the National Bridge Inventory database of the Department of Transportation (DOT), out of a total of 621,510 bridges and viaducts classified in 2023 in the United States, more than 222,000 spans (36% of the total) require significant repair or replacement work, which would cost over $319 billion if addressed this year, compared to the $40 billion over five years planned by the infrastructure plan Job Act launched by the American administration two years ago.

The US bridges in need of the most urgent interventions

In addition to the floating bridge in Seattle, the 2023 list includes the IH 345 crossings on IH 30 and US 75 at Dart Rail in Texas, Route I-678 above the Flushing Bay Promenade in New York, just steps from the sports complex that recently hosted the US Open tennis grand slam. Among the new entries in the report are bridges in North and South Carolina, Oregon, Louisiana, California, and Puerto Rico. West Virginia takes the top spot in the negative ranking, with 20 out of 100 bridges in “poor” conditions, which occur when the deck, substructure, piers, or underground channels have significant structural deficiencies.

In ARTBA’s “poor” ranking, Iowa follows (19%), South Dakota (17%), Rhode Island and Maine with 15% each. Compared to last year, there has been a reduction in bridges in poor condition (560 fewer), and the total has decreased from 42,951 to 42,391. At the same time, however, the category of bridges in good condition has worsened, with almost 1,200 bridges moving into the “fair” ranking. This data, according to the association’s analysis, indicates that there are federal funds available to address non-serious deficiencies, but many states are not taking advantage of them as they could.

Urgent interventions: funds available but not yet allocated

Lined up, the 222,000 spans exceed a length of 6,100 miles, equivalent to a round trip from Boston to Los Angeles. U.S. states currently have access to $10.6 billion in funds from the formula provided in the IIJA Bridge Job Act (which could contribute to necessary repairs on these structures), with an additional $15.9 billion over the next three years. As the end of the fiscal year 2023 approaches, set for September 30, states have committed $3.2 billion, or only 30% of the available bridge formula funds, for 2,060 different bridge projects, with $7.4 billion still available.

Geographically, only eight states have committed more than two-thirds of the funds: Idaho (100%), Georgia (100%), Alabama (97%), Arizona (88%), Indiana (81.5%), Florida (80%), Texas (78%), and Arkansas (68%). There are 31 states that do not reach 33 percent.

ARTBA’s ratings, which bring together the leading companies in the sector committed to improving mobility infrastructure in the United States, including Lane Construction of the Webuild Group, like the Report Cards issued by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), have always been a significant basis for directing the efforts of states and the central administration in road construction, in terms of the environment, safety, and durability.

The future lies in building new bridges

In its latest Report Card for 2021, ASCE noted that as the nation’s bridges continue to age, attention has slowly shifted towards building new bridges rather than maintaining existing ones. The minimum service life has increased from 50 to 75 years, and technical solutions for bridges – as emphasized in the report – favor the use of “materials such as high-performance concrete, corrosion-resistant reinforcements, high-performance steel, composites, and improved coatings to increase resilience and add durability, higher strength, and longer life to bridges.” In addition, “non-destructive evaluation methods and low-impact methods are increasingly used, while new technologies such as infrared thermography, ground-penetrating radar, and remotely managed surveillance devices like flying drones and submarines are implemented to assess bridge conditions and facilitate safer and more efficient engineering decisions.” Last but not least, “living bridges” are being designed in which sensors are incorporated into new and existing structures to provide continuous feedback on structural conditions.