“Back of every great work we can find the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman.” This plaque in memory of Emily Warren Roebling placed on the Brooklyn Bridge in 1951 is probably not a popular selfie spot for tourists, and is unknown to most New Yorkers themselves. But it fully describes America’s pioneer spirit, its ability to pursue impossible projects, and the courage of a woman who made it possible to build the Brooklyn Bridge. This impressive structure opened to the public on May 24, 1883 and has since become a symbol of the infrastructure that has made America great.

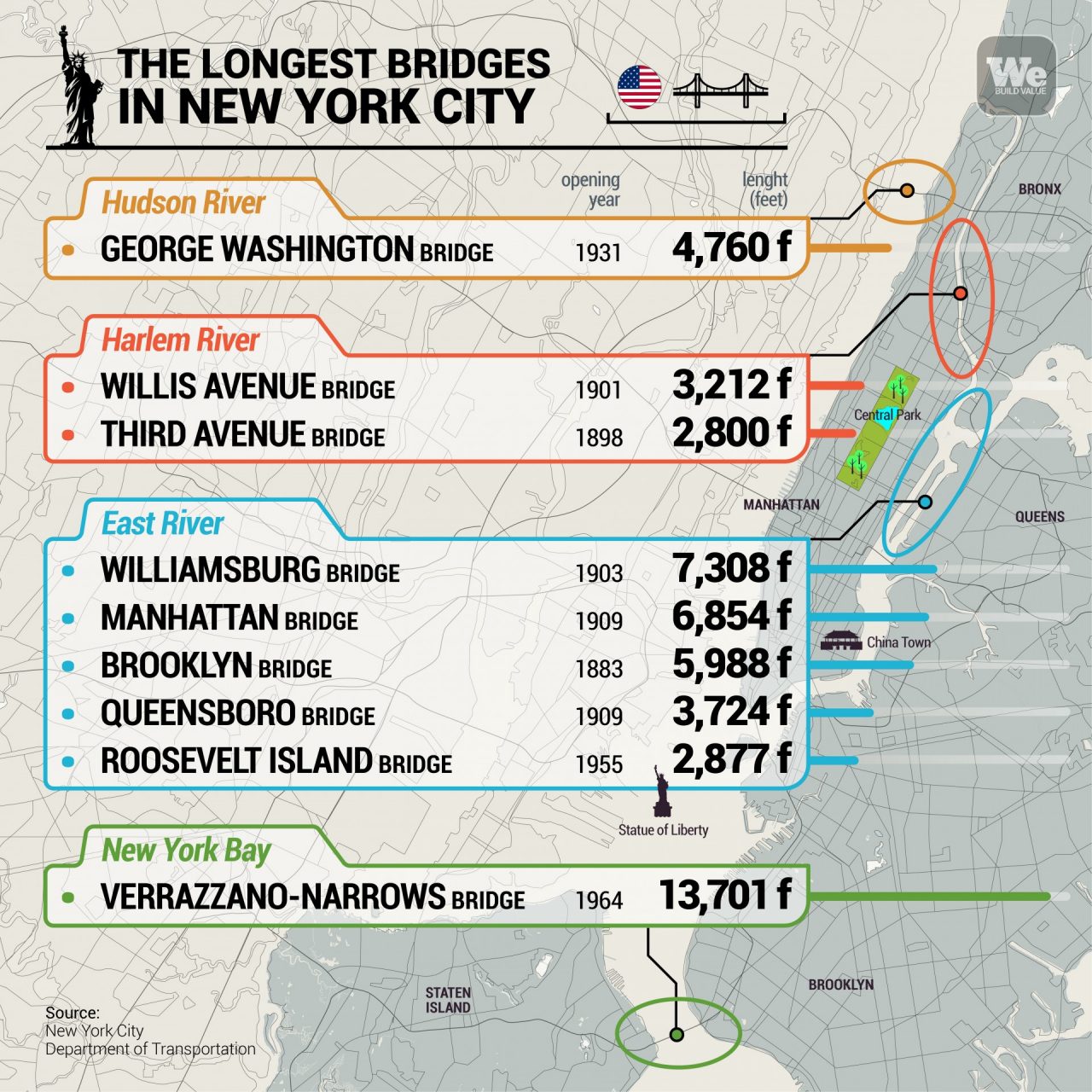

New York has more than 2,000 bridges and tunnels, dozens of which are iconic like the Brooklyn Bridge. The city is an open-air museum of bridges that were futuristic for their time, and many of them are still architectural models today. There is always something magical about a bridge. It is a work of genius, born from the pencil of a visionary and realized with the passion of its builders. These structures are capable of surmounting logistical obstacles, joining the banks of a river, overcoming geological barriers, broadening the horizons of millions of people and improving their mobility. And they are often beautiful as well.

The Brooklyn Bridge, a family business

During the harshest winters of the 19th century, the East River often froze over, making it impossible to cross from the island of Manhattan to Brooklyn by ferry and stranding the growing flow of commuters. On one of those ice-blocked ferries in 1852 was an engineer named John Augustus Roebling with his son Washington, when he supposedly got the idea to build a massive suspension bridge. Roebling had already built smaller suspended structures in North America, and decided to present his steel cable-supported design to the city administration. Such an impressive work had never been conceived before.

Fifteen years later, the approval and the funds to carry out the project finally arrived, and Roebling presented the master plan. But the German-born engineer never lived to see the work begin. In July 1869, Roebling fell ill with tetanus after an accident and died shortly thereafter. Washington, now an adult and an engineer himself, took over from his father in running the project. The first phase involved particularly difficult excavations of the river’s rocky bed in order to support the two giant towers in limestone, granite and concrete. At 85 metres (278 feet), they were far taller than all the other buildings in the city.

Work began just after New Year’s Day 1870, with the laying of immense caissons positioned at a depth of a dozen feet on the Brooklyn side and over twenty feet on the Manhattan side. Air was pumped inside so that workers could excavate the river bottom toiling in harsh conditions, particularly the intense underwater air pressure. When the workers rose to the surface, some become paralysed from extreme decompression sickness, a syndrome called “caisson disease” because it was unknown at the time. Washington Roebling was among those who became paralysed. The project thus lost its chief engineer, the Roeblings’ dream seemed to crumble. Work came to a halt.

And that’s when Emily Warren, Washington’s wife, stepped in to take control of the project. She had studied history and mathematics and had an innate passion for construction. She reassured her husband, and then suppliers and officials that “The bridge will be done!” Newspapers of the time dubbed her the “headstrong bride” and the first woman construction manager. She took civil engineering classes while overseeing materials, analysing the tension of steel cables, managing suppliers, technicians and workers. Washington followed the work from their Brooklyn Heights residence, observing the construction site through a telescope.

After more than ten years of work, the Brooklyn Bridge was opened to the public on May 24, 1883. Emily Warren Roebling was the first to cross it by carriage, holding a live rooster in her lap as a sign of victory. Not all New Yorkers trusted the resilience of this extraordinary bridge. But their perplexity was short lived. Circus master Phineas Taylor Barnum organized a publicity stunt whereby 21 elephants, 17 camels, and other exotic animals crossed over. The two banks of the East River were now joined. Manhattan and Brooklyn begin their journey together as a metropolis. They were soon joined by the other three boroughs, Staten Island, the Bronx and Queens, with the construction of one bridge after another.

Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, the marathon bridge

Every New York City borough has its iconic bridges, and proudly displays them. The various viaducts, cable-stayed bridges, cantilevered bridges, single-span suspended bridges, arched bridges, bridges with steel stays, bridges with magnificent overhanging structures, almost seem to be in competition for the most spectacular crossing. The highest, the longest, the widest — and of course, the most visited and photographed; the ones most frequently chosen by Hollywood for the most romantic scene, the most dramatic car chase, the most reckless leaps. As if to say that there is always a bridge behind a success story.

The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, where the famous New York Marathon starts, connects Brooklyn with Staten Island and was the longest suspension bridge in the world when it was inaugurated in 1964. Today it has been surpassed by a dozen other structures around the world. But it is still the longest in the United States, with its single span of 1,298 metres (4,260 feet). It owes its name to the Florentine navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano, the first European to explore the Atlantic coast from what is now Florida to New Brunswick in Canada, and he discovered New York Bay in 1524.

It is the bridge marking New York City’s boundary with the Atlantic Ocean, and is the only gateway for large ships. Its two towers rise 211 metres (693 feet) high, and have one million bolts and three million rivets. Built to be perpendicular to the earth, they have an overhang between the base and top to accommodate the earth’s curvature. Because of the thermal expansion of the steel cables, the double-decked roadway for cars is 3.66 metres (12 feet) lower in summer than in winter.

Othmar Amman, the designer of the New York City’s bridges

Swiss-born civil engineer Othmar Amman, who co-designed the Verrazzano with Robert Moses, has built six other New York City bridges, including the George Washington Bridge, which opened in 1931 along with his Bayonne Bridge; the Triborough Bridge (1936); the Whitestone Bronx (1939); the Walt Whitman (1957); and the Throgs Neck (1961). The George Washington does not connect two boroughs of the city, but rather two states. It overlooks the Hudson, Manhattan’s west-side river, and joins New York with the state of New Jersey with two-level roadways.

Featured in famous films including “The Godfather,” the George Washington was commissioned by the Port Authority of New York, which today shares management of New York’s bridges with the city’s Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Amman, who became the Port Authority’s chief engineer, designed a 3,500-foot (1,087-metre) span and a pair of 604-foot (184-metre) high steel towers with horizontal steel plate girders. The 260,000-ton concrete anchorage on the New York side and the anchorage on the New Jersey side (drilled directly into the rock of the Palisades cliffs) are joined by four one-foot-diameter steel cables that support the deck. Each is made up of 434 individual steel strands stretched across the span of the bridge 61 times, each time embedded in the anchor before returning. The total length of the steel strands (a bundle of 434 individual cables) is 107,000 miles, or 172,199 kilometres, and from them hang steel suspenders that support the roadway.

This bridge is considered an engineering marvel now more than ever. For years, it has been one of the world’s busiest arteries, with more than 102 million vehicles passing across it annually. On national holidays, the world’s largest American flag flies on the bridge: it measures 90 feet (27 metres) by 60 feet (18 metres) and weighs 450 pounds (204 kg). Another symbol showing that not only is New York “the city that never sleeps”, it is also the city that gives the world engineering marvels born from the courage to design and build.