There are two Japans. There is Tokyo, which is preparing for the 2020 Olympics with a massive infrastructure programme. Then there are the smaller cities and rural areas that are forced to cope with obsolete infrastructure that urgently needs investment.

The alarm was sounded by The Japan Times, which criticised the delay in investments and highlighted the damage caused by 15 typhoons that hit the country this year alone.

Figures published by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan are worrying. As of March 2018, 20% of tunnels, 32% of water sluices and river dikes and 17% of port seawalls were built between the 1960s and 1970s. Their average age, therefore, is 50 years.

The cost to restore all of this infrastructure during the next 40 years comes to 547 trillion yen ($5 trillion), the equivalent of five years of the national budget.

The status of Japan’s infrastructure: Flood risk

Securing rivers from flood risk is the most pressing issue because it is a phenomenon that has worsened in recent years with the increase in the number of typhoons and the amount of torrential rains. Japan has 7,400 kilometres (4,598 miles) of rivers (equal to the distance between London and Kabul). Their banks need to be protected by anti-flooding infrastructure, according to the Shukan Asahi newspaper. The problem affects millions of people: 1.5 million in the Tokyo wards of Adachi, Edogawa and Katsushika facing the greatest risk; and a further 2.5 million people in the greater Tokyo area.

The issue is also a global one, an many large cities have embarked on projects for the virtuous management of water. In Washington, D.C. there is work on a series of hydraulic tunnels such as the Anacostia River Tunnel being carried out by Salini Impregilo that are designed to mitigate sewer overflows that contaminate nearby rivers.

An investment race with China: Japan’s Quality Infrastructure initiative

In the last seven years, the geopolitical challenge between Japan and China has played itself out, to a certain degree, in the infrastructure sector.

As Beijing was investing hundreds of billions of dollars in the Belt and Road Initiative (the construction of transport links between Asia and Europe), Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe responded with an investment plan of $116 billion. The 2016-2020 Partnership for Quality Infrastructure aims to fund new projects in Japan and support the international development of Japanese construction giants. It awards loans to companies that invest in infrastructure projects in Japan and elsewhere, such as Europe. Abe’s idea was not to compete with China’s plan, but to offer countries willing to invest in the sector an alternative that favoured quality over quantity. The first country to sign up was India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi agreed to open the Indian market to Japanese companies that will carry out strategic projects such as the Mumbai-Ahmedabad high-speed railway.

The role of Europe

Europe is playing a strategic role in the infrastructure rivalry between China and Japan. In fact, Chinese President Xi Jinping has extended the Belt and Road Initiative beyond Asia to Europe.

In response to China’s active policy, Japan signed an agreement with the European Union in September for a €60-billion ($65 billion) guarantee fund backed by the EU as well as private investors to develop infrastructure to connect better Asia and Europe and bypass the Belt and Road Initiative. The move has turned Japan into an alternative to China for the development of infrastructure in Asia.

Asia in search of new infrastructure

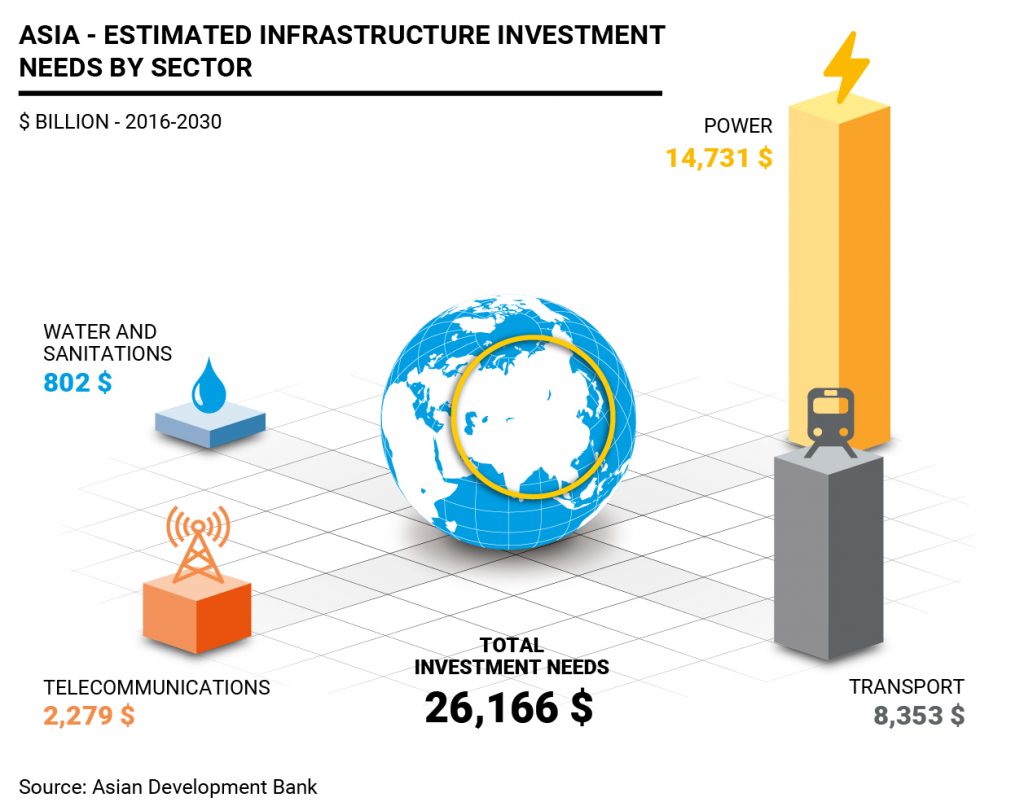

The effort being made by the two countries highlight the continent’s voracious appetite for infrastructure. In 2017, the Asian Development Bank report “Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs” reviewed infrastructure spending demand among its 45 member nations from 2016 to 2030. Including climate-change adaptation, it said $22 trillion in investment for an average of $1.7 trillion per year is needed to maintain the current level of economic growth. Most of these investments will have to be divided between energy and transport, two strategic sectors that support the continent’s economic development.

In essence, the Asian Development Bank said, the infrastructure gap is equal to 2.4% of the continent’s GDP. This is the gap that Japan and China are trying to fill.