On the streets of Dayton, the Covid-19 crisis hangs over the city like a gray cloud. This Ohio city sits in the heart of the U.S. rustbelt, and the economic effects of the coronavirus emergency will probably be felt here more than elsewhere, as the post-2008 slump demonstrates.

Dayton was one of the U.S. cities most affected by the 2008 financial crisis. Even before the outbreak of Covid-19, the poverty rate was 34.5%, average income was lower than the country’s average and the labor force shrank 16% from 2007 to 2017, from 70,255 to 59,114 people employed.

This situation was brought about by factories closing in the city’s historic industries. Now many other cities in the United States risk sharing the same fate, strangled by the Covid-19 lockdown and today desperately looking for a way to safely re-start their economies and avoid recession.

S&P Global has released forecasts predicting the economic impact of this crisis, and reached two conclusions: the economic damage could be three times that of the Great Recession of 2009; the country could recover more quickly from this crisis if it makes heavy investments, particularly in infrastructure.

S&P Global: infrastructure investments to produce wealth

The lines outside soup kitchens on the television news, as well as the exceptional numbers of applications for government financial support submitted in recent weeks, are perhaps the most effective images to illustrate the risks facing the American economy. S&P Global predicts that economic activity in the U.S. will shrink 11.8% in real terms from peak to trough, or $566 billion. Over 30 million jobs will be lost at the trough, wiping out all those created in the last 23 years.

Meanwhile, in the ten years following the 2008 crisis, GDP growth has averaged an annual 2.25%, a third of the rate that the United States recorded in 1959 when President Dwight Eisenhower decided to build the Interstate Highway System.

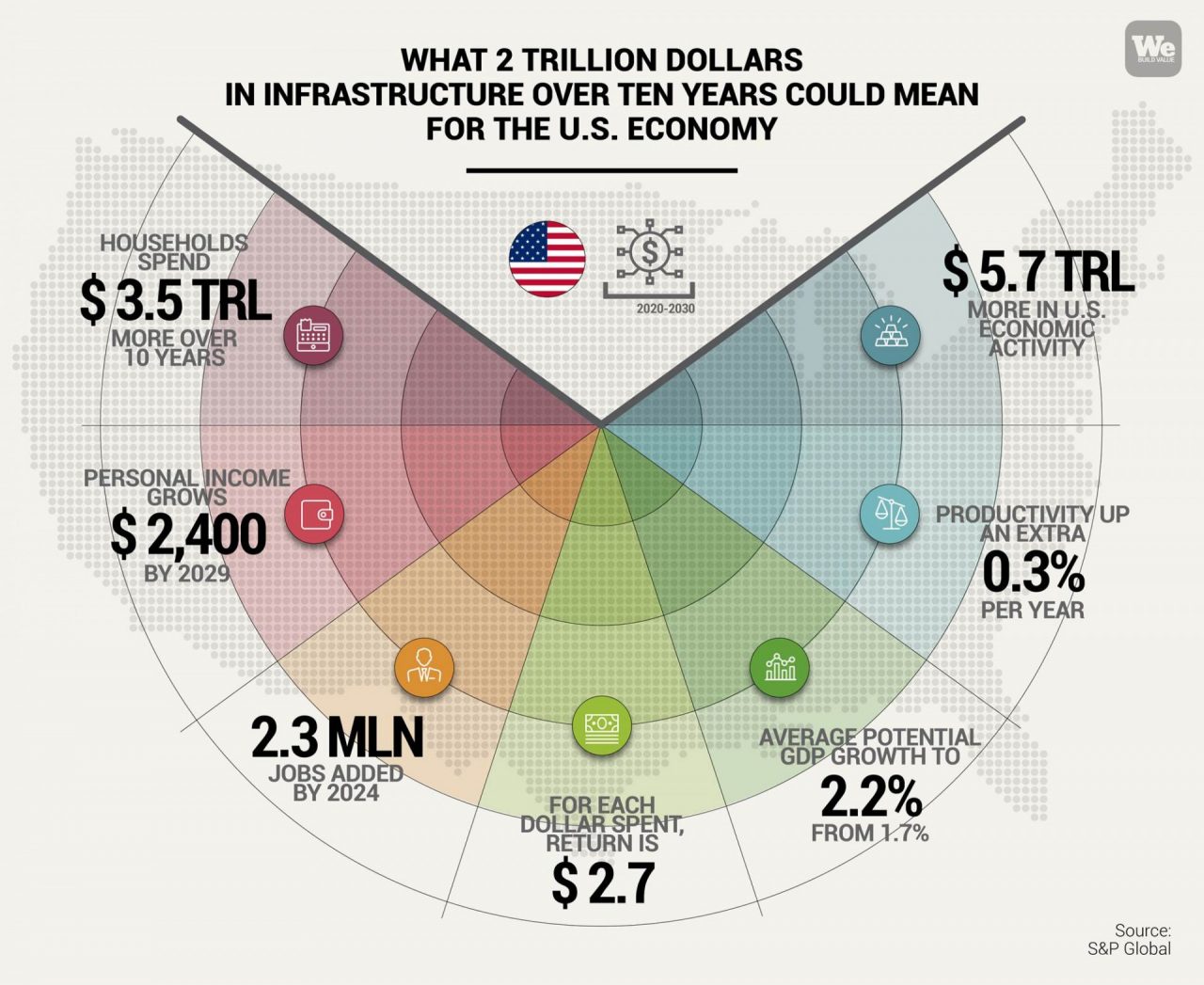

According to an S&P Global report called “Infrastructure: What Once Was Lost Can Now Be Found — The Productivity Boost,” the Great Recession of 2009 was a missed opportunity in terms of creating jobs and stimulating the economy with infrastructure investment. Now the conditions seem to have changed, and the rating company estimates that if the U.S. were to invest $2.1 trillion over the next ten years in the sector (more or less as much as the amount proposed by President Donald Trump) the wealth produced in the economy would reach $5.7 trillion and create 2.3 million jobs already in 2024.

“Covid-19 has created an urgency to invest in much-needed public health infrastructure,” said S&P Global Chief U.S. Economist Beth Ann Bovino in the report. “Six months from now, we may look back on the pandemic as an event like Super Storm Sandy, which called attention to the need for investing in infrastructure to prevent damage from climate change. Either way, it all comes back to infrastructure investment, which we need to tackle now.”

Investing in the country's greatest resource: infrastructure

Looking back at American history, infrastructure investment has always been a key driver for social and economic prosperity in the United States. The California Gold Rush fueled the need to build a transcontinental railway; major public works projects were financed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal; and the Interstate Highway Network created in the late 1950s has become a cultural symbol of the American way of life. These continue to be seen as pillars of this nation’s prosperity, the physical and visible proof of a constant search for progress. This propensity for infrastructure investment has diminished in recent years. And now this vast, historic infrastructure heritage is starting to age.

Yet the coronavirus crisis demands that this trend be reversed. As soon as possible. According to the S&P Global analysis, an increase in public spending on infrastructure could bring American GDP back to the levels reached in the mid-20th century.

“We see infrastructure investment as one way to get the U.S. back on track, once Covid-19 makes its exit, and may even help stave off its next attack!” the report says.

And in fact, looking at the numbers, spending $2.1 trillion in the next ten years on developing new infrastructures and repairing existing ones would also have a boost for GDP, which in that timeframe could potentially jump to an annual 2.2% increase, instead of the 1.7% growth currently expected.

The central issue remains productivity gains, and therefore the ability of infrastructure investments to return to society more than is spent on the construction of major works, like for example President Eisenhower’s highway network. It cost $500 billion to build at current values, and the S&P report cites estimates that for every $1 spent, $6 have ended up flowing back in the U.S. economy in terms of productivity.

Back to the example of Eisenhower

“It’s not too late to be like Ike.” This is the message from S&P Global. The U.S. is still in time to recover from the crisis using infrastructure spending as an economic lever. Here’s how it would look.

If the U.S. were to spend $2.1 billion on infrastructure over the next ten years, the economy would return to pre-crisis levels in a year, instead of seven quarters, said the report. In this scenario, infrastructure spending as a share of GDP would initially reach levels seen during the middle of the last century, and then slow to a higher “steady state” of around 1.8% compared to the 1.3% in 2018 (half of what it was 60 years ago). Personal incomes would grow by $2,400 per capita by 2029, allowing households to spend $3.5 trillion more over that 10-year period than in the “no infrastructure spending” scenario.

From the suburbs of Dayton to New York City, one of the hardest hit cities in the global pandemic, millions of people are waiting for the new era of prosperity to begin. The country now has an opportunity to reactivate an economic motor inspired by the stories and memories of the great infrastructure works of the past that that made America the country it is today. A great national effort to recover from the crisis and, in the worst-case scenario, to be ready for the next hurricane.