“What’s meant by ‘autonomous navigation’?”

“That the captain and crew just watch while the autopilot takes care of everything!”

While automated, electronics-driven boats aren’t that uncommon anymore, a giant, 122,000-ton natural gas tanker, 299 metres (981 feet) long and 48 metres (157 feet) wide, is another story entirely – and a record-breaking one at that. The Panama Canal Extension workers celebrated yet another record with the sixth anniversary of the hefty lock system, built in the Central American isthmus to facilitate transit of huge New Panamax-class ships. The Panama flag waving on the stern of the Prism Courage, which appeared at the Atlantic-side mouth of the canal and later transferred to the Pacific side as it made its way toward South Korea, was the icing on the cake.

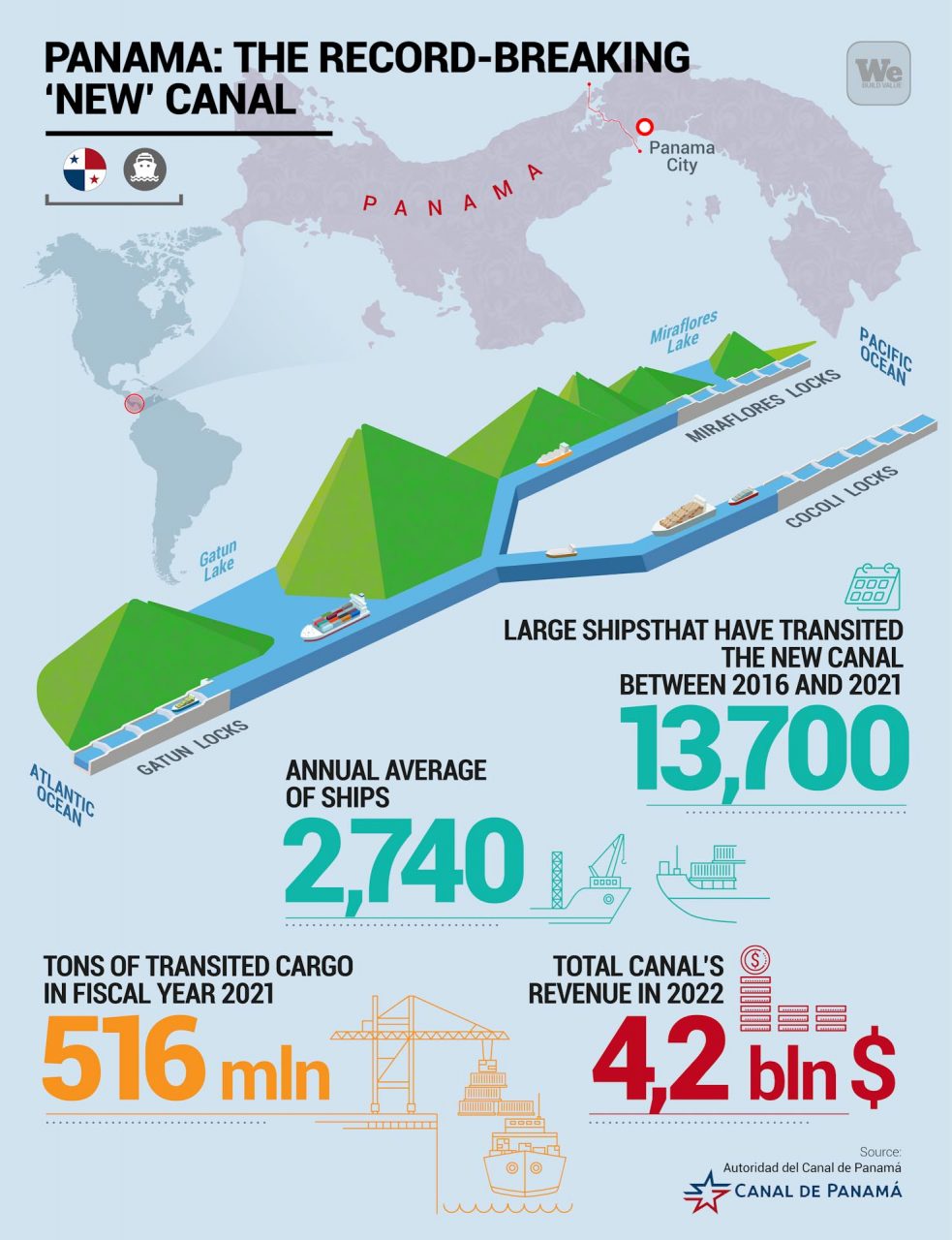

Departing from Freeport, Texas, and bound for the Boryeong LNG terminal, SK Shipping’s Prism Courage, equipped with HD Hyundai autonomous driving systems, is now the first large ship to make an ocean voyage of over 10,000 km (6214 miles) under autonomous control. It will travel nearly 20,000 km (12,427 miles) in 33 days. This feat will include transiting through the Inter-oceanic Canal, which was designed by a consortium of European construction firms led by Webuild, and inaugurated on June 26, 2016 with the voyage of the Cosco Shipping Panama, bound for China with a record-breaking 9,443 containers on board. But that number was surpassed in just six years of operations of the most acclaimed engineering work in recent history.

The impact of the new Panama canal on global trade

This incredible infrastructure was designed to protect the sustainable development of the Isthmus of Panama, implementing technology that saves up to 60% of the water normally used in ship transit. The structure was also designed for optimal safety, reducing travel time while simultaneously increasing ship carrying capacity threefold compared to the original canal, which opened in 1914 and is still operational for smaller ships. It was also built with the express purpose of benefiting Panama’s economy and growing revenue.

Concrete data came early and exceeded even the most optimistic expectations. From the opening day to September 30, 2021, at the end of the last fiscal year, 13,700 large ships passed through the new Panama Canal Authority-commissioned project, with an annual average of 2,740 ships. That’s 7.6 ships per day – the project was initially expected to see an average of 5-6 ships per day.

The new Panama Canal, which was needed for an ambitious maximum cargo peak of 12,000 containers, now regularly sees 15,000 containers transit through – that’s one and a half times the cargo of Cosco Shipping Panama six years earlier. In May 2021, a 370.33-metre (121-foot) New-Panamax ship set a new record for the largest ship to transit through the new lock system. The Canal Administration could then declare the Canal transitable by 96.8% of the world’s commercial fleet.

In fiscal year 2021, the Panama Canal, between old and new locks, set a record of 516.7 million tons of transited cargo, up 8.7% from the previous year and 10% from 2019. 2022 figures are expected to rise significantly. The most conservative estimates still predict a 3.6% increase by the end of the year, or at least 535 million tons.

An economic driver for Panama

The Canal’s revenue totaled $3.98 billion (€3.71 billion) up from about $2 billion (€1.9 billion) prior to the opening of the new locks. Based on these results, Canal management expects $4.2 billion (€3.9 billion) in revenue for 2022, a projection that far exceeds the estimates made at the opening. Initial projections were for doubled revenue in the first five years and exceeding $5 billion (€4.6 billion) in total canal revenue by 2030.

The main goal of the Panamanian government was to bring Panama back to the center of global maritime trade. It was to return it to being a key global shipping crossroads, reversing the trend of ignoring this waterway. This drop in relevance had been fueled in part by rapid growth in ship size, particularly on the Asian side, and in part by the ways the old U.S. military-engineered locks reflected the era in which they were made and did not have the depths needed for today’s “sea giants.”

Building the new canal: a monumental undertaking

The construction of the new Canal was a huge undertaking, involving more than 30,000 workers and technicians over seven years of work. The project aimed to protect the rainforest eco-system during excavation. CO2 emissions were also drastically reduced due to streamlined maneuvering times and increased ship cargo capacity.

The new New Panamax locks are 427 metres (1401 feet) long, 55 metres (180 feeet) wide and 18.3 metres (60 feet) deep. The chamber system for the passage of ships from one ocean to another is regulated by 16 massive steel gates (8 for each ocean entrance). Constructed by Webuild-led companies, they weigh about 4 tons each and can open and close in less than 5 minutes during the required processes for transiting ships from one chamber to another.

Design choices were sustainability-led, even before today’s infrastructure demands called for it. A notable development: raising the ships above ocean level. In three stages, ships gradually reach the 27-metre (89 foot) height of the Gatún reservoir, located within the isthmus, and then move back down to the level of the second ocean, without any engines or energy-consuming systems. In fact, the Canal only relies on gravity and water pressure to move the ships. With the new canal, the average crossing time from one ocean to the other is 8-9 hours (whereas the old Canal’s average was 13 hours).

The Canal’s impressive results were also on full display to delegates at the first international forum to honor Panama as the “New Economy Gateway Latin America.” Sponsored by Bloomberg, the forum was held on May 18, just weeks before the Canal’s sixth anniversary. “Panama has long been a critical link between continents, helping Latin America unite North and South,” Michael Bloomberg said in a welcome address to speakers.

That connection became even clearer to forum participants due to a viral photograph of the long but orderly line of ships waiting for the green light to enter the new Panama Canal. As many as 101 vessels – many of them from Asia – were filled to the brim with goods of all kinds for American markets. On the one hand, the photo offered fresh talking points for the forum on the global distribution chain crisis and the supply difficulties plaguing consumers, deliveries, and prices. But on the other, as it was noted at the symposium, those ships confirmed Panama’s promising future, and it has seen record quantities of goods pass through the new locks in recent weeks, with the reopening of some markets between China and the United States, such as grain, pork, and liquefied natural gas.