From the United States to Australia, and from Europe to the Middle East, half the world’s shipyards are keeping a close eye on developments at the port of Shanghai, the heart of global trade. Raw materials such as iron and aluminum, essential to the construction of large-scale infrastructure works, as well as strategic goods for much of world industry, depart from Shanghai.

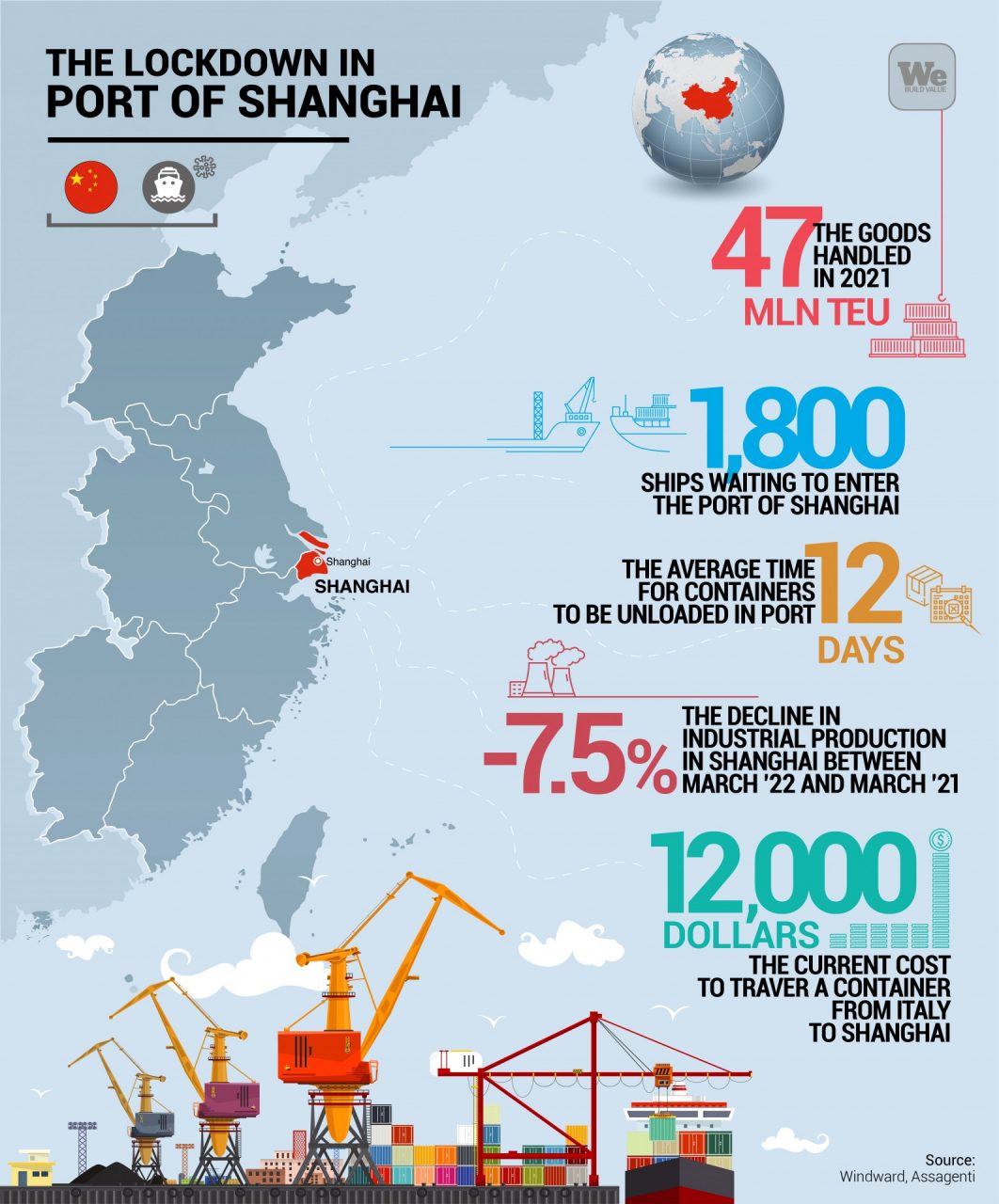

Home to 30 million residents, Shanghai also hosts the world’s largest marine terminal, which handled 47 million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit, a standard measurement used for cargo) in 2021.

After an initial slowdown due to the war in Ukraine, the port’s activities have now taken a hit from Covid-19, due to Shanghai’s recent uptick in cases.

The Chinese government has already fought hard against the virus, so authorities have been implementing increasingly strict measures. According to logistics analysis company Windward, the heightened controls have resulted in 20% of the world’s 9,000 active container ships being blocked in the roadstead of Shanghai as they wait for the green light to enter the port.

Ships blocked in Shanghai port, commerce interrupted

Shanghai’s expanded lockdown was announced on April 5, when the number of cases began to rise. Since then, the port authorities have adopted new access-related restrictive measures. Every week, according to Windward, about 500 ships arrive and are forced to stay at anchor, waiting to get the go-ahead to enter.

On average, a container arriving today in Shanghai will wait an estimated 12 days before being loaded or unloaded by a ship. The usual wait time is closer to 5 days. To avoid a full port closure, Chinese authorities have created “worker bubbles” for employees, who are currently working and residing in the infrastructure, reducing contact with the outside and mitigating contagion risk.

In spite of this, the effects have been felt across many sectors, not just the infrastructure world. Tesla, the Californian car company that produces electric cars in both the United States and in China, told Bloomberg that the Shanghai funnel has, to date, cost a month’s worth of work.

The Continental Group, one of the largest car part manufacturers, also announced that transportation delays at the Shanghai junction will result in a cut in growth forecasts for all of 2022, which will stop at +5%, rather than the +8% forecast at the beginning of the year.

Shanghai gets to work on restarting and the first signs of recovery are appearing

The industrial production figures reflect the state of affairs in Shanghai better than perhaps anything else. In March, these figures fell by 7.5% compared to the same month in 2021, also a difficult year for Covid-19. The effects of the Chinese government’s “Zero-Covid” policy, which uses what some see as drastic measures to curtail any new spread of the virus, have been felt in the economy of a megalopolis that today generates 5% of the entire country’s GDP. Though the crisis is not yet over, the first signs of recovery are appearing. Vice-mayor Zhang Wei stated recently that 70% of the area’s 666 multinationals have declared that they’ve restarted production, since the port continues to ensure the transport of key materials for world production, albeit slowly.

Certainly, the funnel effect on the major commercial port of call has caused a substantial increase in costs. Assagenti, the association of Genoese shipping agents, reports that before Covid, transporting a container from Italy to China cost $1,500 (€1,422); today this has gone up to $12,000 (€11,380). These costs are reflected in the raw materials, essential for the construction of large-scale works in Italy and in the world. These works are currently key to the economy’s revival and modernisation.