Looking down from the top, you get the impression you are about to make a bungee jump into the void; this point is high in the mountains, squeezed between the steep cliffs of the Apennines and suspended over the waters of the Favazzina River as it runs towards the blue Calabrian sea.

The sense of vertigo is inevitable when you cross the Favazzina viaduct, one of the most complex engineering works on the Salerno-Reggio Calabria motorway, as it floats across the valley at a height of 150 metres (492 feet) – about half as tall as the Eiffel Tower.

The viaduct, built by the Webuild Group, is located in the heart of the barren and unspoiled Apennines, just a few kilometres from Scilla, one of the most beautiful seaside resorts in Calabria.

Its reconstruction was a fundamental milestone in the modernisation of the Salerno-Reggio Calabria motorway, confirming the viaduct’s strategic value for transport in Italy’s south. The old viaduct was designed in 1974 by engineer Riccardo Morandi, who also built the Genoa bridge that collapsed in 2018. And like the original viaduct, the new Favazzina crosses the mountains inside two tunnels, the Brancato on the Reggio Calabria side and the Muro on the Salerno side.

A flying highway that overlooks the valley, cutting the mountains in two.

Favazzina viaduct’s technical profile

At 2 p.m. on March 5 2013, the last section of the northern carriageway of the viaduct was opened to traffic. This important moment marked the end of work on one of the most complex sections of the new Salerno-Reggio Calabria: five tunnels and seven viaducts one after the other.

Among these, the Favazzina viaduct is one of Europe’s most admired feats of civil engineering because of its size, characteristics and environmental complexity. And like the famous Millau Viaduct in France (for years the highest in the world standing 269 metres, or 882 feet, above the valley floor), Favazzina was designed to become the flagship of a motorway already well-known for its high-altitude journeys. The old Salerno-Reggio Calabria — with the Bagnara bridge, the Viadotto Italia, the Serra and the Rago — has for years boasted the most head-spinning altitudes for viaducts of any highway in the world.

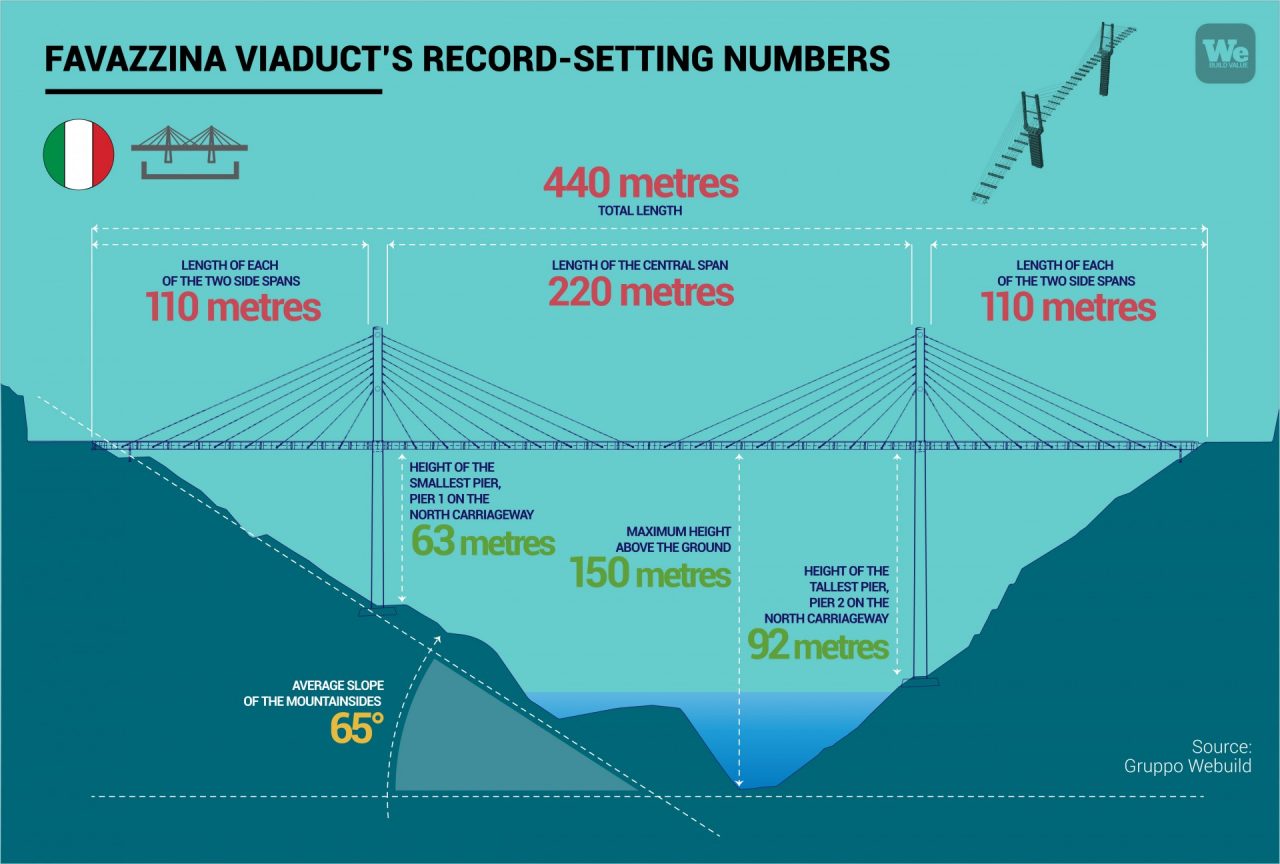

The Favazzina viaduct is 440 metres (1,443 feet) long, divided into a central span of 220 metres (721 feet) and two side spans measuring 110 metres (360 feet).

The route of the bridge is curvilinear from beginning to end, while the deck is made with a mixed system of steel and concrete, and is supported above the void by huge piers that look like well-planted giants. Pier 2 of the south carriageway, the smallest of all, is 54.6 metres high, or 183 feet. Pier 2 of the North carriageway reaches a height 91.9 metres (300 feet).

The complexities of the site

An invisible thread connects the construction of the Favazzina viaduct with the history of some of the most important works built and under construction by the Webuild Group in Italy.

This thread is made of technology, engineering challenges and technical skills, but also personal experience. Surveyor Umberto Russo, who is currently finishing up the construction of the new bridge in Genoa, was technical director of the Favazzina viaduct from April 2010 to December 2011.

Then there is the story of engineer Antonio Franzese, who in 2012 became technical director of Favazzina and today holds the same position on one of the two lots of the Naples-to-Bari high-speed train line being built by the Webuild Group.

Like many other infrastructure works built in Italy, the Salerno-Reggio Calabria viaduct was technically very complicated, and is considered one of the most complex engineering challenges Italy ever faced.

“The most difficult thing was to reach the places at the bottom of the deep, narrow valley where we had to prepare the foundations for the piers,” recalled engineer Antonio Franzese. “In order for the cement mixers to get all the down there, we had to dig a road. If were couldn’t have done it, we would have had to bring the cement down by cable car.”

Environmental sustainability linked to the project

The unpredictability of nature was an often-incalculable factor that further complicated construction. At Favazzina, both mountainsides have slopes with a grade exceeding 65 degrees, and are covered by mobile material like dirt and vegetation. Besides this, working at the bottom of the valley was almost impossible, partly because of its characteristics and partly to preserve the natural beauty of an area that could not be violated by a construction site.

“The Salerno-Reggio Calabria project included environmental protection measures, checked and approved by the Ministry of the Environment,” says Franzese. “There was a huge effort of forest restoration, for which oaks, chestnut trees, and olive trees that grow in the area were re-planted. In the Favazzina valley, the riverbed and the two mountain slopes which had been affected by the construction work were restored. And even where the old viaduct used to stand, we replanted trees.”

Lastly, to protect the environment and stabilize the Reggio Calabria side, a “net” about 80 meters (262 feet) long was strung up on the mountainside, held down to the ground by 10,000 nails. An unusual but inevitable solution so that the new viaduct could “cling” to the steep slopes of the Apennines.

Working safely, without looking down

The height of the viaduct, combined with the shape of the long, narrow valley, required the site to adopt a series of safety measures that went beyond those mandated by law.

With piers almost 100 metres (328 feet) high, and on a deck that reached 150 metres (492 feet) above ground level, the worksite called for a creative approach.

The barriers installed to protect workers from falling from the worksite at those great heights were 1.5 metres (4.9 feet) high, instead of the regulation 1 metre (3.2 feet) And a safety net was positioned below the entire length of the site, designed also to have a psychological impact on the workers, blocking the view and therefore minimising the risk of panic linked to high altitudes. All were necessary precautions taken to allow the new viaduct to “float” between the steep mountains of the Apennines.

“Getting to the end was very exciting,” says Franzese today. “I’m not really sure back then we realized the importance of what we were doing. I was just trying to do my best as a young engineer. Instead, looking at it today, I realize that we created a very beautiful and unusual infrastructure work.”