It was the Millennium Drought, which plagued so many regions in Southeast Asia and Australia, that forced Melbourne to strike back by investing in strategic infrastructure to make the city safer for its 4.5 million residents.

During the most difficult months of the Great Drought, when Melbourne’s water reserves dwindled to 28.4% of total needs, plummeting by 20% in a single year, the government announced plans to build a desalination plant that could treat seawater capable of ensuring the city’s drinking water needs in the future.

In June 2007, former Victoria Premier Steve Bracks first spoke about plans to build a plant in Dalyston, in the southern part of the state, called the Victorian Desalination Plant. The goal was to protect the city from drought, but also to help disseminate a new water treatment technology that would be used in many Australian cities. The Victoria state government unveiled its broader “Our Water, Our Future” plan, which has put a series of infrastructure projects (dams, treatment plants, new networks) for more efficient use of water at the centre of the political agenda.

Victorian Desalination Plant: Australia's largest desalination plant

The Wonthaggi Desalination Plant (as the plant is also called) is Australia’s largest in terms of treated water capacity. The work, built with an investment approaching AU$4 billion, has a very complex structure that runs from the sea to the edge of Melbourne. The desalination plant is connected on one side with a marine plant through a network of pipes up to 2 kilometres long and on the other side to Berwick, near Melbourne, where the treated water is pumped. An 84-km underground pipeline carries the water from the plant to Melbourne, while the plant is powered by an 87-km underground power link that is fully offset by renewable energy credits. One of the main features of the plant is its “green” roof, the largest of its kind in Australia, made of biodegradable materials that create a thermal coat, reduce the risk of corrosion and the number of maintenance operations required.

Seawater treatment is conducted through the technique of reverse osmosis, the same used in many desalination plants around the world, starting with those built by Webuild Group’s Fisia unit, one of the world leaders in the sector.

The impact of the work on Melbourne’s daily life

Despite the complexities in terms of the work, its impact on the city is enormous: the plant is capable of pumping 150 billion litres (39 billion gallons) of potable water into Melbourne homes each year. The amount of treated water is equivalent to 60,000 Olympic swimming pools and equal to about one-third of the metropolis’ total annual needs. This allows the treated water to be used partly to supply the city and partly to create useful reserves in the event of drought and water crisis.

The plant is the largest water infrastructure work in Melbourne’s recent history after the Thomson River Dam was completed in 1983. From that year to 2007, the region’s water reserves fell from 97.8% of annual needs to just over 20%, confirming the devastating impact that drought on the one hand and population growth on the other have had on the city’s water supply.

Australia embraces desalination

Desalination is an increasingly strategic industrial solution to respond to the constant water crises affecting many dry regions of the world, such as Africa and the Middle East, or developed areas such as California or Australia which are hit by violent drought waves.

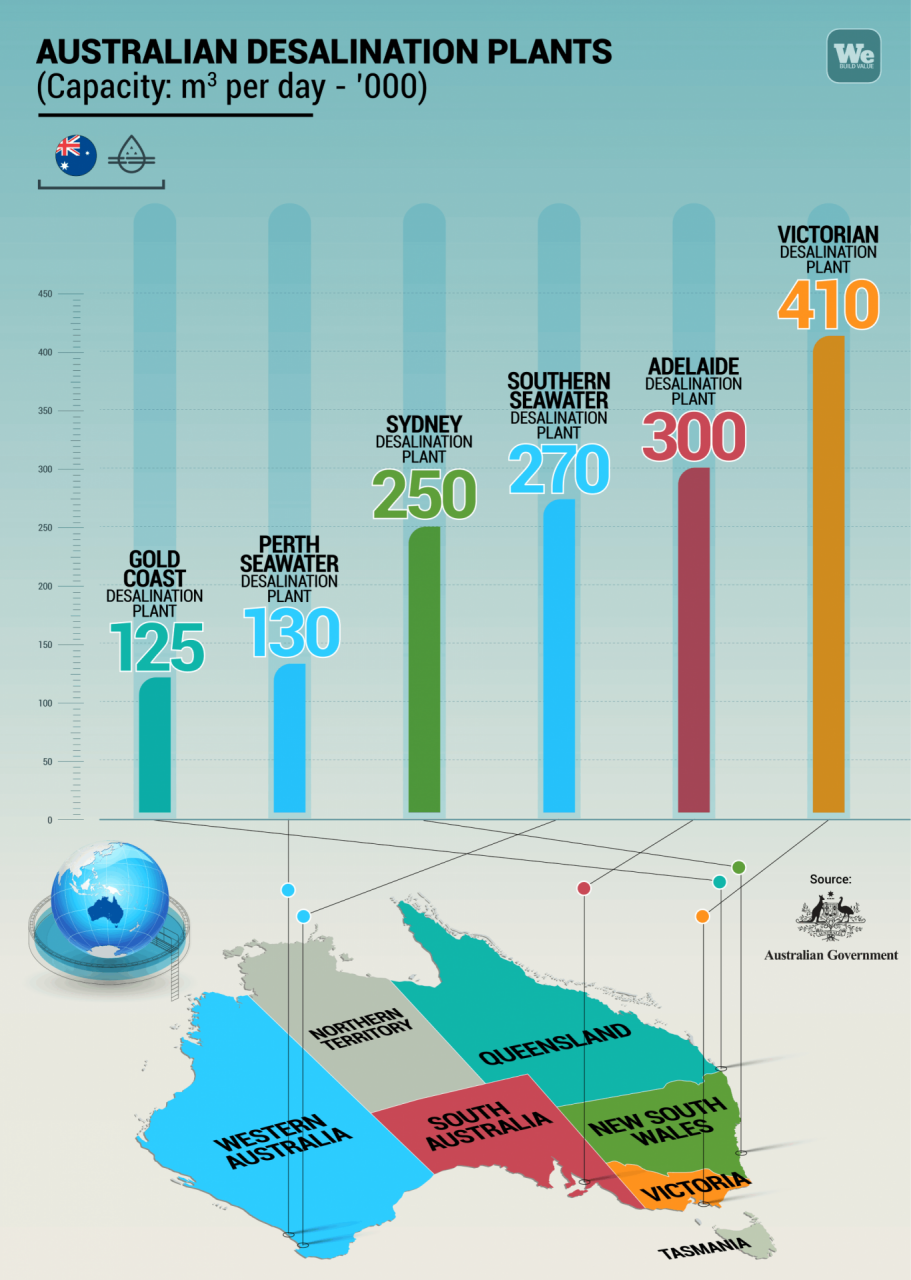

To date, according to Global Water Intelligence data, the largest producer of desalinated water in the world is Saudi Arabia with 22.9 million cubic meters per day. It is followed by the United States (15.5 million cubic meters) and China (12.2 million cubic meters). In Italy, the Webuild Group, through its subsidiary Fisia Italimpianti, has launched the “Water for Life” project, proposing the construction of new plants. Australia is also investing heavily in this technology. In addition to the Melbourne plant, over 30 plants are now active in the country, some of them large ones such as the Perth Seawater Desalination Plant (completed in 2006) serving the city of Perth. The same applies to the Kurnell Desalination Plant, which with its capacity to produce 250 million litres (66 million gallons) of potable water per day provides 15% of Sydney’s water needs. Overall, almost all the plants are powered by renewable sources, mostly wind power, confirming the sustainable inspiration of these works so essential to meeting people’s water needs.