Pennsylvania is looking for clean energy. In the state with Philadelphia as its capital, squeezed between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic ocean, the York Energy Storage company has announced the intention to build a large dam with a hydroelectric plant on the Susquehanna river, in York county.

The project envisages a $2.1 billion investment to build a dam 3,000 meters long (1.9 miles) and 70 meters tall (225 feet), creating a basin of 242 hectares (598 acres), thus efficiently managing the river water on one hand and fueling the hydroelectric power plant on the other, producing clean energy.

York Energy Storage expects the hydroelectric power plant of the dam to produce 8,560 megawatt hours in a ten hour cycle, enough to satisfy the needs of a city with half a million people. The project is in its infancy but it sparked the attention of the media and public opinion because it reopens the debate on great dams, which today are more essential than ever before to manage water, especially in light of the crisis due to droughts and floods.

The need for dams to face climate change

In the US, Lake Mead is an emblematic example. Given the continuing drought, the largest artificial water basin in the country, created by the Hoover dam, has fallen to historical lows. This led to the construction of a new basin capable of managing the water at the bottom of the older basin and ensuring Las Vegas’ water supply. One of the most complex engineering projects of its kind in the world, it was realized by the Webuild group, a world leader in the water sector and also active in the construction of large dams.

Lake Mead’s case, and that of many other American lakes and rivers, (see the lowering of the Colorado river) have convinced many observers of the need to invest again in infrastructures capable of managing water in the best possible way.

According to a study by the United Nations University’s Institute for Water, Environment and Health, while towards the late 1970s there was a peak of 1,500 dams build in a year around the world, in 2020 only 50 were built. At the same time, a UN report warns that “tens of thousands of existing large dams have reached or exceeded an ‘alert’ age threshold of 50 years, and many others will soon approach 100 years. These aged structures incur rapidly rising maintenance needs and costs while simultaneously declining their effectiveness and posing potential threats to human safety and the environment.”

Investments and maintenance to renovate old dams

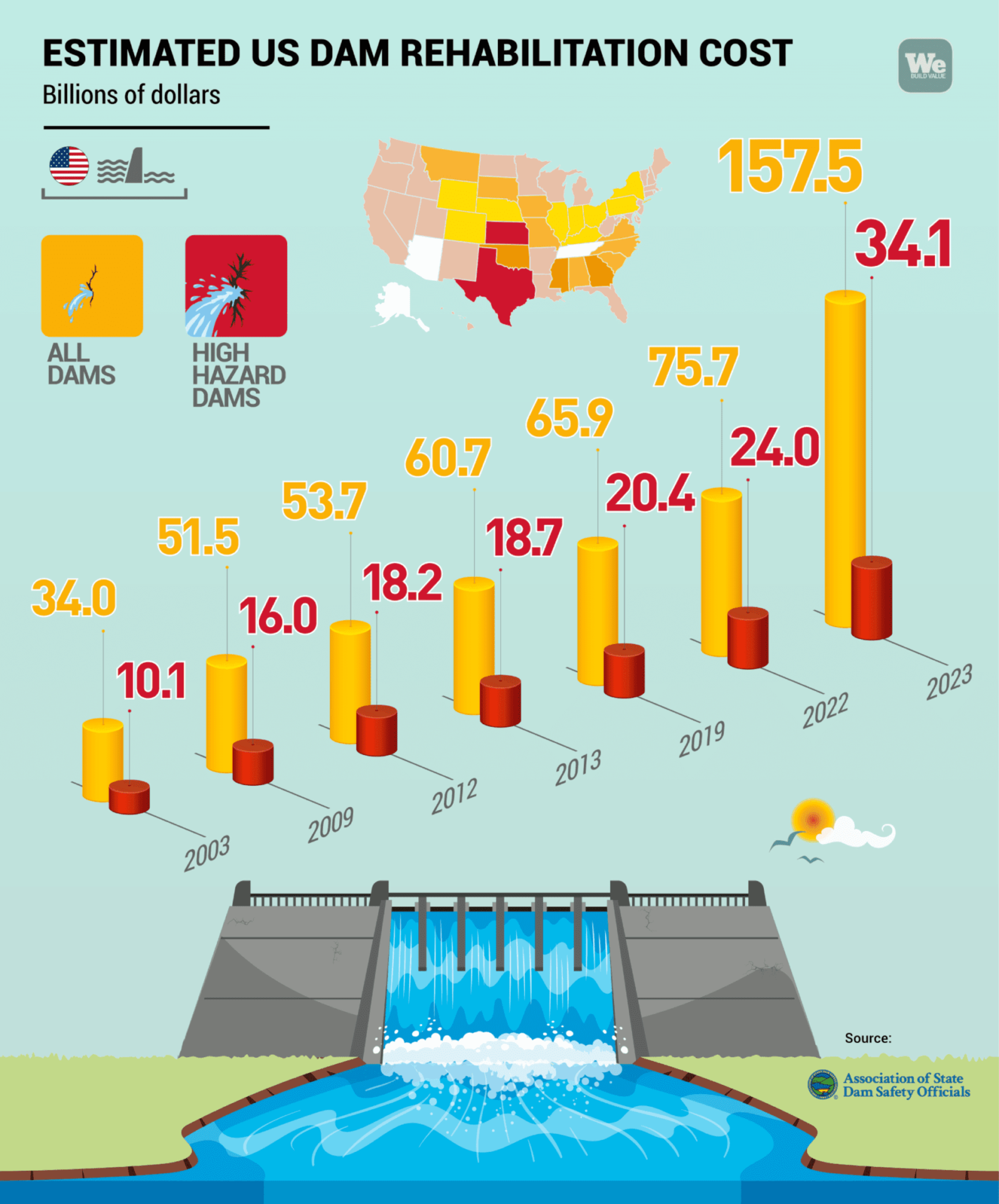

The age of these giants capable of producing clean energy brings up the issue of economic resources and investments. A report by the US Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates that $157.5 billion are necessary to modernize the 88,616 non-federal dams needing work done today. The Association also says $34.1 billion are needed just to ensure the safety of the most critical dams. The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act earmarked funds for dam maintenance, but the $4 billion set aside for the next five years are still too little compared to real needs of the country.

In the meantime, several projects have begun in the US to remove the oldest dams. Of these, the most significant is that of the Klamath river dam, between California and Oregon. Many still remember the Oroville dam accident when, in 2017, faced with the risk of collapse of part of the dam, US authorities had to evacuate 200,000 people. And in 2019 a violent storm caused the Spencer dam to collapse in Nebraska. Maintaining old dams and at the same time building new, more modern ones remains an imperative to guarantee people’s safety and to spread infrastructures capable of producing clean energy.