For many, liquified natural gas has replaced oil as the world’s new energy “gold.” This commodity has become even more valuable after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the halt in Russian gas supplies to Europe. And so liquefied natural gas may become Europe’s answer to the energy crisis that threatens millions with a colder and poorer winter.

From Italy to France, from Germany to Spain, major European countries have moved to open new channels of exchange with liquefied natural gas producers, starting with Qatar (where the world’s largest field is located) and ending with the United States.

The issue, however, is not just about the raw material. The right infrastructure is needed to store, receive and transport it, from ships to ports. A new round of investments is needed to complete the energy transformation that a system based on historical pipelines — for years the protagonists of gas supplies mainly from Russia – with new infrastructure that can transform the liquid gas and transport it to where it is needed.

The leaders in liquefied natural gas

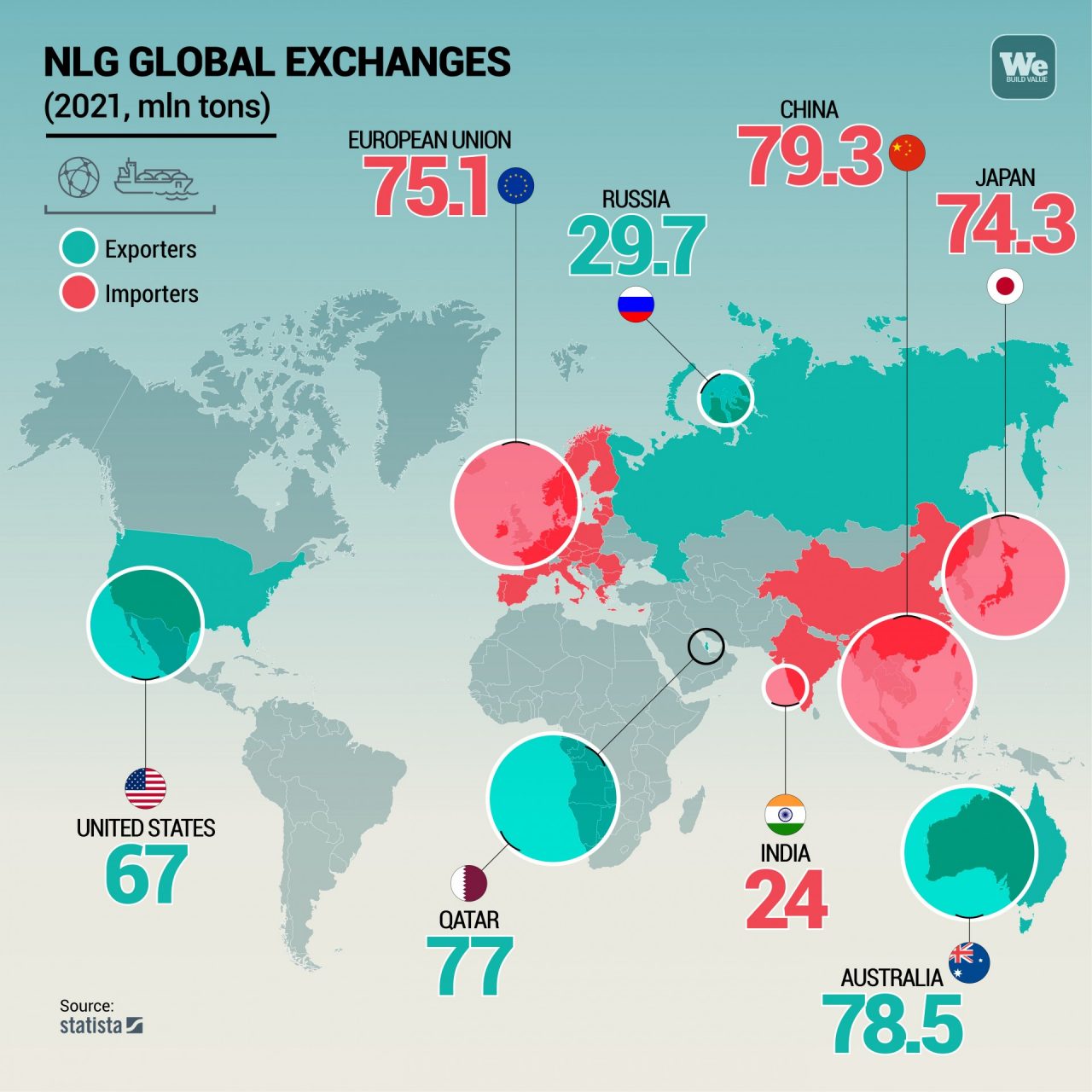

In recent months, European governments have embarked on consultations and diplomatic meetings with the leading liquid gas exporters. According to international statistics in 2021 Australia and Qatar dominated the market, supplying 40% of the total cargoes crossing the seas (with 78.5 million tons for Australia and 77 million for Qatar). Right behind them was the United States of America, which instead exported 67 million tons of liquefied gas, 16 million of which ended up in Europe.

In 2022, the U.S. commitment to supply Europe has grown. Last March, U.S. President Joe Biden signed an agreement with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen committing Washington to supply more gas to Europe. And in the first six months of 2022, loads from America had already exceeded the 2021 total. The U.S. is thus aiming to replace Russia, and in fact, according to a report by EWI, the Institute for Energy Economic Studies at the University of Cologne, the U.S. could reach 110 million tons per year of gas exports in 2030, 90% of the gas Moscow was selling to Europe before the outbreak of war. Qatar also plays an important role in this scenario despite the fact that its traditional market in Southeast Asia is where it now sells almost all of its gas.

Europe goes hunting on the world gas market

The almost complete breakdown of diplomatic relations with Russia has removed it from its role as Europe’s most important gas supplier. That is why in recent months the continent’s chancelleries have traveled far and wide to sign new agreements to purchase this crucial raw material. This is an uphill climb because Europe is still far behind other countries in its consumption of liquefied natural gas. In 2021 – according to analysis by the World LNG Report – China and Japan together purchased the same amount of LNG as the whole of Europe. Beijing alone imported 79 million tons, when Spain and France stopped at 13 million each, and Italy at 6.8 million. The war tipped these balances and brought Europe to the forefront of the buyers’ market. It is a crowded and expensive market where, however, economic resources are not enough. Infrastructure capable of handling the arrival of the new “gold” is also needed.

Ports and ships, those strategic liquid natural gas infrastructures

The Ministry of Infrastructure’s call for proposals to build natural gas processing plants, refueling points at natural gas ports, and purchase ships to enable bunkering activities expired on September 10 for a total of €220 million, financed from the resources of the National Supplementary Fund (created to invest alongside Italy’s EU-funded Covid recovery plan, the National Resilience and Recovery Plan, or NRRP). The announcement is just one of the Italian government’s responses to the gas crisis. In fact, Snam, the state-controlled company that manages Italy’s gas pipelines, has completed the purchase of two regasification vessels that will come into operation between 2023 and 2024.

On the ports front, on the other hand, NRRP funds include investments of €3.8 billion, which are to be allocated to strengthen sustainability, electrify docks, and increase last-mile road and rail infrastructure. Of this, nearly €2 billion will be allocated to the South. Many ports are affected, including the strengthening of the Aosta breakwater in Naples, the docks of the new Ro-ro terminal in Cagliari, and the expansion of the port of Brindisi. A separate chapter concerns the construction of a new breakwater in Genoa, which many see as one of the most important projects of the NRRP. To be built by a consortium led by Webuild, the breakwater will allow the Ligurian port to be transformed into one of the main European ports of call. Along with the rest of the projects, this will also help increase Italy’s infrastructure capacity in terms of handling shipping traffic, changing the paradigm and the country’s role in continental trade. From cargo to gas.